In The following is an article I wrote about my theories regarding electrical brain stimulation, which I believe may provide a useful treatment for the COVID symptom known as brain fog.

Abstract

Neurological disorders with symptoms such as chronic pain, depression, and insomnia are widespread. Very weak electric fields applied through the skull can enhance or diminish neural activity and modulate brain waves in order to treat many of these common medical problems. This approach is to be contrasted with well-established pharmacological methods or more recent invasive electrical deep brain stimulation (DBS) techniques that require surgery to insert electrodes deep into the brain. We claim that non invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) will provide new treatment methods with much greater simplicity, lower cost, improved safety and in some cases, possibly greater effectiveness.

Methods of stimulating the brain are based on emerging electro-technologies

such as transcranial DC/AC electric fields and pulsed magnetic fields. The application of functional and time-dependent brain imaging methods can be used to locate relevant brain regions, and determine the most appropriate stimulation method. The application of tailored and individualized control can be combined with other therapy methods to effectively treat neurological disorders while minimizing or even eliminating the use of pharmaceuticals.

This emerging use of NIBS is a branch of a new multidisciplinary field that we

coined Neurosystems Engineering (Yonas and Jung 2008). This field involves

neuroscientists, psychologists, and electrical engineers. This emerging field

relies on existing standards for the safe implementation of these novel treatment modalities (Wassermann 1998). We must emphasize, however, that the characteristics of intensity, frequency spectrum, electrode configuration, duration, and repetition of treatment are being actively studied through empirical methods. We anticipate that the application of modeling and simulation of these methods for specific problems will result in more effective treatment methods and matured standards of care. Nevertheless, this emerging medical application of electrotechnology has shown the potential to have an enduring impact on society.

Introduction

We are entering a new era of neurological modification through direct communication with the brain via electrical stimulation. This era follows closely the “pharmacological” era in which modification of brain functioning was achieved through tinkering with various neurochemicals, most notably dopamine and serotonin. This tinkering led to profound changes in the ways in which both mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia) and neurological disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s disease) were treated. Before 1950, most psychiatric patients were treated with institutionalization, lobotomy, or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). With the advent of Thorazine around 1950, pharmacological control of psychosis was possible. Similarly, in 1950, levodopa was first demonstrated to reduce Parkinson symptoms in animals. Unfortunately, all of these chemical interactions with the brain have broad effects, and the possible harmful side effects often compete with the efficacy of treatment (Tschoner, Engl et al. 2007).

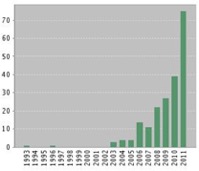

The brain communicates both chemically and electrically (Hausser, Spruston et al. 2000); however, recent advances within the neurosciences have led to a resurgence of interest in electrical stimulation to modulate brain functioning in health and disease (Fregni and Pascual-Leone 2007). The promise of electrical stimulation lies in more tailored intervention, applied to relatively discrete neuronal populations, over set time intervals. This promise has led to a dramatic increase in research, in the last two decades, across a wide range of psychiatric, neurological, and normal population cohorts (Figure 1). In contrast to early studies where mere application of electrical stimulation was found to be generally efficacious (see next section below), the advent of modern neuroimaging and neuroscience techniques have allowed researchers to delve into underlying mechanisms, allowing for increasing levels of “fine tuning” and engineering of current timing and spatial distribution as increasing knowledge is gained.

Figure 1. Number of electrical stimulation studies by year (tDCS, tACS, tRNS, TMS). (Acronyms defined later in the text.)

Figure 1. Number of electrical stimulation studies by year (tDCS, tACS, tRNS, TMS). (Acronyms defined later in the text.)

A Brief History

The idea of using electricity to treat various medical conditions dates back to 43 AD, when Scribonius Largus, described a detailed account of the use of the (electric) torpedo fish to treat gout and headache. Since that time, numerous scientists experimented with electrical stimulation in hopes of treating various maladies as well as attempting to bring people back from the dead. It was the invention of the battery that made DC stimulation possible.

The history of electrical stimulation as a method for investigating the functions of the nervous system began with the Italian scientist Luigi Galvani (1737-1798). He discovered in 1786 that nerves and muscles are electrically excitable. In a series of experiments that revolutionized neurophysiology, Galvani was able to elicit contractions in the muscles of frogs by stimulating them or their spinal nerves with brief jolts of electricity generated by static generators. It was only after scientists developed apparatuses to allow for a more controlled and accurate way of stimulating biological tissue that scientific progress became more rapid, and that systematic studies of nervous function became possible.

After Galvani’s results were confirmed, scientists became convinced that nerves and muscles were electrically excitable, and that they also generated a kind of electricity by themselves. This could be the basis for a new model of nervous activity. Thus, two questions became highly important at the time: i) are the spinal chord and brain substances also electrically excitable? ii) could the stimulation of different points in the brain generate different effects or in different parts of the body? The first scientist to test this hypothesis of differential stimulation, was Giovanni Aldini (1762-1834). He used the bodies of recently hanged prisoners to apply electrical currents and demonstrated movement and responses, but he was actually stimulating the muscles directly.

At this point in history, the idea to apply electrical stimulation directly to the exposed brain was the next logical step. The first to do this was Luigi Rolando (1773-1831). In 1809, Rolando carried out several experiments stimulating the surface of central nervous structures. Using a Voltaic pile and crude electrodes, he obtained limb movements, which became stronger in the vicinity of the cerebellum. He erroneously concluded that this structure was the brain’s “source of vital motor energy.”

Rolando was thus able to provide a satisfactory answer to the first question only, i.e., he proved that the central nervous system was indeed electrically excitable, and that Voltaic stimulation could be a valuable research tool for exploring brain functions. The answer to the second question would have to wait 40 years, until better stimulation techniques could be discovered, with finer control over duration, intensity, and area of stimulation.

These techniques were developed on the basis of the advance of knowledge about electromagnetism. Between 1845 and 1850, other electro-physiologists developed a great diversity of devices and techniques to carry out single or repetitive stimulations, with short pulses or trains, and a finer control over current intensity and duration. Repetitive trains of stimulation with a precise onset and offset were generated by rotary switches and mercury pool switches, or electromechanical metronomes. The stimulation of the surface of the cerebral cortex by using brain stimulation was used to investigate the motor cortex in animals by researchers such as Eduard Hitzig (1838-1907), Gustav Fritsch (1838-1927), David Ferrier (1842-1928) and Friedrich Goltz (1834-1902). The human cortex was also stimulated electrically by neurosurgeons and neurologists such as Robert Bartholow (1831-1904) and Fedor Krause (1857-1937). In the following century, the technique was improved by the invention of the stereotactic method by British neurosurgeon pioneer Victor Horsley (1857-1916), and by the development of chronic electrode implants by Swiss neurophysiologist Walter Rudolf Hess (1881-1973), José Delgado (1915-2011) and others, by using electrodes manufactured by straight insulated wire that could be inserted deep into the brain of freely-behaving animals, such as cats and monkeys. This approach was used by James Olds (1922-1976) and colleagues to discover brain stimulation reward and the pleasure center. Little real progress was made until the 1950’s with the use of noninvasive electrical stimulation by Russian scientists in research they called “Electrosleep” (Rosenthal and Wulfsohn 1970). Since then there has been a steady increase in global interest in the subject using transcanial magnetic stimulation (TMS) as well as transcranial DC and AC stimulation (tDCS and tACS).

Recently Emerging Methods

tDCS

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is the application of weak electrical currents (1-2 milliAmp) and induced electric fields in the brain of order 1 Volt/m to modulate the activity of neurons in the brain (Nitsche et al. 2008). Several generations of neurophysiological experiments have shown that neurons respond to static (DC) electrical fields by altering their firing rates. Firing increases when the positive pole or electrode (anode) is located near the cell body or dendrites and decrease when the field is reversed (Wagner et al. 2007). However, when the electrodes are placed on the scalp, the current density produced in the brain is exceedingly small, changing membrane potentials only by a fraction of a milliVolt.

Much of the current is shunted through the skin and within the brain, through the cerebral fluid thus limiting the effect on neurons (Wagner et al. 2007). In the 1960s, a few reasonably well-controlled experiments suggested that electrodes placed on the forehead produced noticeable psychological changes that were dependent on the direction of the field. Priori et al. in 1998 provided the first demonstration that weak direct current delivered over the scalp can influence the excitability of the underlying cerebral cortex. In 2000, Nitsche and colleagues at the University of Göttingen expanded the findings of Priori et al. by demonstrating that anodal polarization of the motor cortex increased the motor response of transcranial magnetic stimulation of the same area even after the current offset; reduction of this response was observed with cathodal polarization. Moreover, these effects were reported to last for an appreciable amount of time after exposure. Investigators are currently testing the validity of these claims and the effects of tDCS on other brain areas and functions.

DC brain polarization is not “stimulation” in the same sense as the stimulation of the brain and nerves with conventional electrical techniques at much higher electric fields. It does not appear to cause nerve cell firing on its own and does not produce discrete effects such as the muscle twitches associated with classical stimulation. It is also important to distinguish it from electroconvulsive therapy, which is used to treat mental illnesses such as major depression by passing pulses of approximately 1 Amp and fields of 1000 Volt/m into the brain in order to provoke an epileptic seizure. One of the first clinical applications of tDCS was for treatment of hemiparesis (motor paralysis) following stroke. Currently tDCS is being studied for the treatment of a number of conditions including stroke, migraine (DaSilva et al. 2012), and major depression.

Figure 2 presents one manner in which tDCS can be applied to a subject and Figure 3 describes the modulatory effects of DC fields on neuronal firing. Depending on the polarity of the tDCS electric fields, neuronal firing can either be enhanced (anodal) or suppressed (cathodal).

Figure 2. Example of a commercial tDCS unit (http://www.neuroconn.de/dcstimulator_plus_en/).

Figure 2. Example of a commercial tDCS unit (http://www.neuroconn.de/dcstimulator_plus_en/).

Figure 3. The modulatory effects of DC fields on neurons. When aligned with the neuronal potentials, firing is enhanced (left); when opposed to the neuronal potentials, firing is suppressed (right). (Courtesy E.M. Wassermann.)

Figure 3. The modulatory effects of DC fields on neurons. When aligned with the neuronal potentials, firing is enhanced (left); when opposed to the neuronal potentials, firing is suppressed (right). (Courtesy E.M. Wassermann.)

It is important that the tDCS device is current-controlled. What this means is that the device will adjust the voltage up and down as the resistance changes so that the current never changes. For instance, if the resistance of the circuit including the skin, the skull, the cerebral fluid, and the brain matter is 1000 Ohms, then a 1.0 Volt source will produce a current of 1 milliAmp and a small fraction of that will reach into specific areas of the brain.

In the first placebo-controlled study of stroke, anodal tDCS applied over the motor cortex resulted in improvement in the affected hand in every patient tested (about 12% improvement on average) (Hummel, Celnik et al. 2005). Subsequent studies found cathodal (but not anodal or sham) stimulation over the left frontotemporal region to improve naming of line drawings in a small (N = 8) group of patients with expressive language dysfunction due to stroke (Monti, Cogiamanian et al. 2008). Based on these clinical results, studies have been undertaken in healthy subjects, designed to improve associative verbal learning (Floel, Rosser et al. 2008) as well as motor skill (Boggio, Castro et al. 2006), and even memory formation (Reis,

Robertson et al. 2008). While anodal stimulation is most often used, more recent studies are focused on cathodal administration to dampen effects of hyperactive neuronal populations in epilepsy (targeting the epileptic focus) (Fregni, Thome Souza et al. 2006) and migraine (targeting the occipital cortex) (Chadaide, Arlt et al. 2007; Antal, Kriener et al. 2011). tDCS studies have accelerated in the last decade (Figure 4), with nearly 38% of the total studies (N=76) occurring in 2011 alone.

Studies are being undertaken to modulate the effects of tDCS with various drugs designed to either enhance or suppress the stimulation effects. For example, neuroplasticity after-effects appear to be N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) specific (Liebetanz, Nitsche et al. 2001) as opposed to acute effects (Nitsche, Seeber et al. 2005); therefore, application of tDCS in the presence of NMDA receptor (d cycloserine, amphetamine) and GABA (lorazepam) agonists have been found to facilitate the after-effects of tDCS application (Nitsche, Liebetanz et al. 2004). Targeted therapies wherein pharmacological and electrical stimulation are combined to achieve optimal dose-response relationships in diseases including pain management (Antal, Brepohl et al. 2008), epilepsy (Nitsche and Paulus 2009), and even Alzheimer’s disease (Ferrucci, Mameli et al. 2008; Freitas, Mondragon-Llorca et al. 2011) represent important and exciting areas of future development in brain stimulation.

Figure 4. Number of tDCS studies by year.

tACS

Relatively few studies of transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) have been undertaken, a technique designed to change intrinsic cortical oscillations. The current can be applied to the earlobes or the sides of the head, known as cranial electrotherapy stimulation – CES (Zaghi et al. 2010). This technique opens up the possibility of actively synchronizing cortical rhythms through external means particularly when administered in the so-called “ripple” frequency range (between 100 and 250 Hz) associated with memory encoding (Moliadze, Antal et al. 2010). This technique must be used at relatively low frequencies or retinal flashes will be induced; moreover, at higher amplitudes, safety concerns – including seizures – remain. In spite of these very particular reservations, active synchronization of cortical oscillatory activity provides particularly enticing possibilities regarding very fine-tuned experiments involving stimulation, behavior modification, recording of neuronal activity, and alteration of stimulation in real time. Currently, the tACS method is primarily used to treat depression, anxiety, and other mood related disorders.

tRNS

The most recent player to the electrical stimulation field is transcranial Random Noise Stimulation (tRNS). This method, akin to adding “white noise” to ongoing neural activity, is thought to open ion channels at the neuron (Schoen and Fromherz 2008). In one of the first studies in normal human subjects, stimulation over the motor cortex (between 100 and 640 Hz for 10 minutes at 1.5 mAmp) was found to increase cortical excitability (Terney, Chaieb et al. 2008). These authors hypothesize that, like tACS, tRNS “can possibly interfere with ongoing oscillations and neuronal activity in the brain and thus result in a cortical excitability increase.” There are several potential advantages of tRNS over tDCS: 1) while tDCS can open ion channels once, tRNS can do so repeatedly through multiple ionic influxes; 2) tRNS works around problems associated with stimulation of different sides of a folded cortex which can lead to effects which cancel each other out; 3) tRNS does not create a “tingling” sensation, as does tDCS when applied; 4) safety concerns are minimized. A recent study found superior performance of high frequency (100 – 640 Hz) tRNS over tDCS (1.5 mAmp) in normal subjects on a perceptual learning task (Fertonani, Pirulli et al. 2011). A second study did not find improved performance of tRNS over tDCS in normal subjects on a working memory paradigm (Mulquiney, Hoy et al. 2011). Only a handful of studies have been undertaken with tRNS; however, this technique appears to combine the main benefits of both tDCS (e.g., ionic influx/neuronal excitation) and tACS (e.g., entrainment of oscillations) without many of the potential downsides (e.g., burning, retinal stimulation, possible seizures, etc.).

TMS

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a noninvasive method to excite neurons in the brain: weak electric currents are induced in the tissue by rapidly changing magnetic fields (electromagnetic induction) (Lefaucheur 2009). This way, brain activity can be triggered with minimal discomfort, and the functionality of the circuitry and connectivity of the brain can be studied. The principle of inductive brain stimulation with eddy currents has been noted since the 19th century. The first successful TMS study was performed in 1985 by Anthony Barker et al. in Sheffield, England. By stimulating different points of the cerebral cortex and recording responses, e.g., from muscles, one may obtain maps of functional brain areas. By measuring functional imaging (e.g. MRI) or EEG, information may be obtained about the cortex (its reaction to TMS) and about area-to-area connections.

Repetitive TMS stimulation is known as rTMS and can produce longer lasting changes. Numerous small-scale pilot studies have shown it could be a treatment tool for various neurological conditions (e.g. migraine, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, tinnitus) and psychiatric conditions (e.g. major depression, auditory hallucinations). TMS is becoming more widely used for treating nonresponsive severe depression.

Figure 5 shows how the TMS coil produces that fields that noninvasively interact with the brain. A TMS coil suspended over the brain. The time-changing magnetic field (red) induces the electric field and currents (green) in the brain. (Courtesy E.M. Wassermann.)

Figure 5 shows how the TMS coil produces that fields that noninvasively interact with the brain. A TMS coil suspended over the brain. The time-changing magnetic field (red) induces the electric field and currents (green) in the brain. (Courtesy E.M. Wassermann.)

Applications

In the last 20 years, the use of noninvasive electrical brain stimulation (NIBS) has transitioned from the ad hoc use of a variety of techniques and methods to a more systems engineering approach to achieving desired methods to treat neurological disorders tailored to specific problems and individual characteristics (Priori 2003). We have described this approach to the combination of neuroscience, psychology, and electrical engineering as the new field of Neurosystems Engineering (Yonas and Jung 2008). We believe this new multidisciplinary engineering approach will have a profound and lasting impact on serious health problems. Our specific and original concept is a systematic combination of methods described in the last section, tACS, tRNS, and real time control to achieve major cognitive benefits. This is to be compared with prescriptive application of NIBS, or the use of pharmacological prescriptions that treat disease, but create undesirable outcomes: neither are individualized to the disorder or the individual except through a process of trial and error. We are proposing an approach based on treating specific problems from a Neurosystem Engineering point of view.

A Neurosystems Engineer approaches the solution to problems through first focusing on the specific problem, and then applying the scientific method of hypothesis, experimentation, data collection, and modification of the process and the hypothesis until a consistent explanation is achieved in order to solve the problem. We believe this approach resulted in our thinking about tailored contorol to focus the dose, duration, frequency spectrum, and electrode geometry to deal with the individual and the disorder. Individualized treatment approaches, using neuroimaging, are beginning to be used in the field of ECT (Ujkaj, Davidoff et al. 2012), and we believe that this approach can be applied more broadly and with a high degree of fidelity.

We propose to do more than merely stimulate the brain and observe and

diagnose the resulting change in behavior, but to measure the effect on brain function in real time by measuring the electrical signals from the brain (via EEG/MEG) and controlling the stimulation to achieve the desired change in the time dependent brain waves that we determine, through experimentation, are critical to diagnosis and treatment of the disorder. This point of view is very

different from the conventional view that brain disorders are neurochemical abnormalities that can be best treated by changing brain chemistry. It is reasonable that there will be neurochemical changes associated with the changes in brain wave characteristics, and these longer lasting neurochemical changes will be important to both measure and modulate as has been recently demonstrated with glutamate and GABA (Stagg, Best et al. 2009). This approach may augment or replace traditional pharmaceutical or prescriptive NIBS approaches, with application of feedback controlled NIBS achieve desired efficacy for disorders that are more prone to “treatment resistance” (e.g., insomnia, anxiety, depression).

For example, one common form of insomnia is caused by irregularities in the restorative slow wave portion of the sleep cycle characterized by powerful oscillations at less than 1 Hz (Bonnet 1986). Our Neurosystems Engineering approach would be to entrain that frequency through tACS in order to achieve restorative sleep (Zaehle et al. 2010). Similarly, the calm thinking achieved in a meditative state is characterized by 10 Hz oscillations and we would hypothesize that anxiety reduction could be achieved by inducing oscillations at that frequency.

An increasingly common disorder is depression, a disorder that been correlated with a lack of long term sustained oscillation at 5 Hz, (Linkenkaer-Hansen et al. 2005) as well as abnormally high levels of theta oscillations (Lewine 2012). We would hypothesize that application of that frequency over a controlled period would achieve an improvement in depression symptoms. In these three applications we have focused our attention on a specific portion of the brain wave temporal spectrum rather than focalization on a specific brain region. It may also be useful to use brain imaging, such as fMRI or MEG, to determine the primary brain region of interest and use finite element modeling to optimize the electrode configuration to achieve optimal results (Bullard, Browning et al. 2011; Clark, Coffman et al. 2012).

One serious argument against this NIBS approach to neurological treatment is that we are changing the frequency spectrum only temporarily, and long-term characteristics have not yet been resolved. We know that there are neurochemical effects that accompany the changing frequency spectrum (Clark, Coffman et al. 2011), and the result of the electrical and chemical change can lead to retained brain network changes, called plasticity, that result in a remembered functional process. We hypothesize that the electrical brain stimulation can train the brain to continue operating in the desired manner and that this memory effect is an adjunct of the individual motivation. We are proposing the use of electrical brain stimulation as a “brain builder” dependent on the motivation of the patient.

The stimulation input can be achieved through various means described above of introducing controlled electric fields in the brain. The least invasive approaches are through inductive coupling from a changing magnetic in a coil near the scalp, or through an applied electric field through conducting electrodes in contact with the scalp. Much more invasive stimulation has been achieved through electrodes surgically implanted in the brain (deep brain stimulation), although there are obvious reasons to focus on non-invasive methods that have been developed. They all stimulate neurons to become more or less active but they do not cause neuronal firing, since they operate at applied fields of 1-10 Volts/m, which are a factor of ten below the self firing from potential developed across the neuronal membranes within the brain. The electrical excitation approaches are typically applied with a current limiting circuit and a voltage of less than 10 Volts driving currents of roughly one milliAmp to the scalp with electrodes of a few cm2.

We propose to avoid the possibility of seizure in all of our approaches and do not consider ECT, which produces fields in the brain of 1000 Volts/m driven by an external source of hundreds of volts. We are not emphasizing the use of DC electric fields, which can either sensitize or desensitize (i.e., polarize) a portion of the brain but not entrain brain waves. Instead we believe that major advances in neurological treatment can be achieve through brain wave modulation through time dependent electric fields resulting in changes that are monitored in real time in order to modify the stimulation amplitude and frequency spectrum. Laboratory experiments have already shown brain wave entrainment in animal models and humans (Zaehle et al. 2010), and the ability to cause the brain circuits to synchronize to an applied frequency has been well established (Anastassiou et al. 2011 and references therein). Recent work with tRNS has shown the ability to modulate, directly, brain wave spatial synchronization, by applications of high frequency, to enhance synchronization throughout the brain (Fertonani, Pirulli et al. 2011). We hypothesize that a combination of tACS to achieve a modulation at a desired frequency and tRNS to enhance spatial synchronization will lead to improvements in efficacy and efficiency. We also believe that what is needed are applications of closed-loop feedback control to demonstrate the levels needed for individual treatment of specific disorders in specific patients. We believe that individual treatment for specific disorders will require tailored waveforms, dose, and stimulation configurations to achieve optimum results.

Conclusions

We believe that this Neurosystems Engineering approach will provide improved understanding of many neurological disorders and the ability to achieve real improvements in a nonpharmacological, painless, low cost, and practical approach that will have an enduring impact on society. Future advances in this electrotechnology must be achieved in coordination with the standards community.