In my last post I claimed that success in missile defense will depend on the trustworthiness of key people involved in the development of the system software. No problem if everyone involved swears they can be trusted. But how do we know if any individual is really a bad guy who is lying? Bring on Wonder Woman’s lasso of truth, if you believe in comic books. But wait, there is more. The inventor of that magic rope also invented the polygraph that measures the physiological responses of the test subject under questioning.

But wait, there is more. The inventor of that magic rope also invented the polygraph that measures the physiological responses of the test subject under questioning.

This polygraph approach is the gold standard of deception detection in most high security institutions, such as the CIA, but what does perspiration or blood pressure have to do with lying? Well, there is a connection if false answers go along with stress.

This polygraph approach is the gold standard of deception detection in most high security institutions, such as the CIA, but what does perspiration or blood pressure have to do with lying? Well, there is a connection if false answers go along with stress.

The best liars, however, can be very cool and persuasive if they really believe in their view of reality. The best validation of this is from George Costanza of “Seinfeld.” He stated quite correctly, “If you believe it, it is not a lie.”

Given this ability to trick a lie detector, it seems reasonable to keep looking for the magic rope and that may come from the new field of neurosystems engineering, as documented in my course Introduction to Neurosystems Engineering available on iTunes at https://itunes.apple.com/us/itunes-u/introduction-to-neurosystems/id575671935.

It is possible that high spatial and temporal brain images could show indications of “guilty knowledge” that combined with prior knowledge of the subject could lead to a real lie detector. Brain research is progressing rapidly, and some day we might be able to better deal with bad guys working on critical software, but for now, the best approach is the skilled boss who gets to know the employee. Failing that, we must test the defense system extensively, but still be prepared that the hidden bug could get turned on only when the real attack occurs.

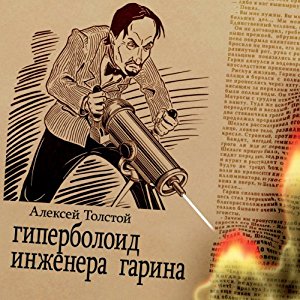

story about the genius inventor Garin described a weapon with pinpoint, but still incredibly destructive, capability. This prophetic novel not only predated by decades the invention of the laser, but it also quoted Garin’s detractors as claiming, “This invention smells of higher politics.”

story about the genius inventor Garin described a weapon with pinpoint, but still incredibly destructive, capability. This prophetic novel not only predated by decades the invention of the laser, but it also quoted Garin’s detractors as claiming, “This invention smells of higher politics.” launch vehicle Energia. The payload for the launch was the 80 ton Polyus experiment dedicated to the development of a space control laser weapon. Polyus was a giant risk that was characteristic of the Soviet experimental technology philosophy of try it, learn from failures, fix it and try again. The huge gamble had been in the works as a multiyear high power laser program that was already underway but became a crash program in response to Reagan’s SDI initiative. Instead of trying to compete with their own space-based missile defense program, they decided that laser-based space control would be the most logical path to defeat the SDI. Gorbachev knew that even a minimally successful deployment and test would lead to a space weapon race with the United States. He knew that his failing economy and inferior computer and electronics technology would certainly just accelerate the Soviet path to failure. Fortunately Polyus failed to orbit because of a software problem, and a real star war was avoided.

launch vehicle Energia. The payload for the launch was the 80 ton Polyus experiment dedicated to the development of a space control laser weapon. Polyus was a giant risk that was characteristic of the Soviet experimental technology philosophy of try it, learn from failures, fix it and try again. The huge gamble had been in the works as a multiyear high power laser program that was already underway but became a crash program in response to Reagan’s SDI initiative. Instead of trying to compete with their own space-based missile defense program, they decided that laser-based space control would be the most logical path to defeat the SDI. Gorbachev knew that even a minimally successful deployment and test would lead to a space weapon race with the United States. He knew that his failing economy and inferior computer and electronics technology would certainly just accelerate the Soviet path to failure. Fortunately Polyus failed to orbit because of a software problem, and a real star war was avoided.