With the advent of the Covid lockdown in 2020, I decided to try my hand at writing science fiction, as an activity to maintain some semblance of sanity. Based on my experiences in the Pentagon, national labs, and consulting for the government, I wrote about the fictitious discovery of an unlimited, cheap, safe energy source. The result was a series of technothriller novels, called the Project Z series. The first book, The Dragon’s C.L.A.W., will be published this May.

Now, you may ask, how much of this series is based on reality? How close are scientists to creating the ultimate energy source? Recently, as my book headed to print, scientists achieved a major fusion breakthrough at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. This fusion research program exists to support the nation’s nuclear weapon program, but the breakthrough made headlines because of the potential to use fusion as an alternative energy source.

On Dec 13, 2022, Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm, announced an outstanding scientific and technical achievement. Lawrence Livermore’s device, called the National Ignition Facility (NIF), had demonstrated “fusion ignition” in a laboratory for the first time. The machine had created a nuclear reaction that generated more energy than it consumed.

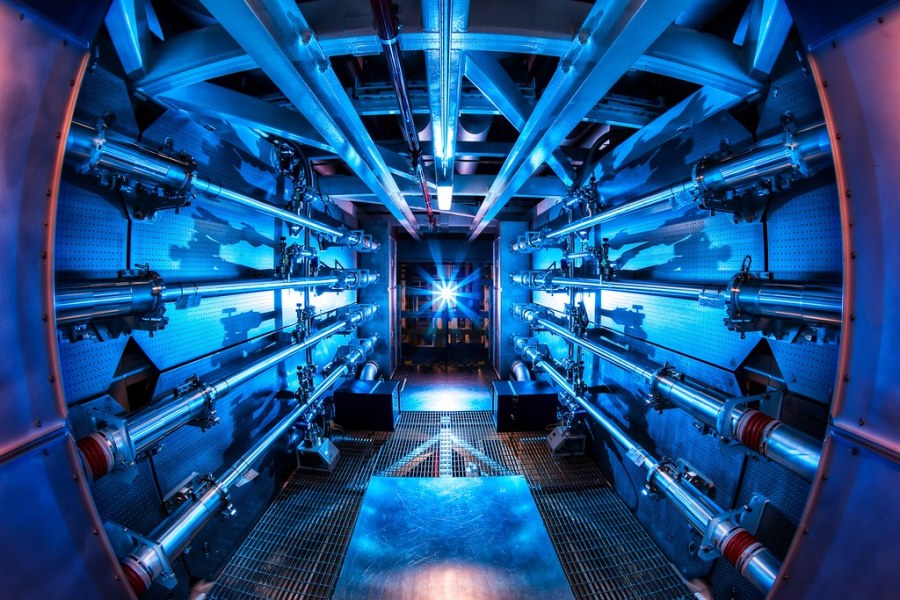

Construction on NIF began in 1997 and the device started operating more than 10 years ago. The machine takes energy from a giant capacitor bank, as large as an apartment building, and transforms that energy into 192 pulsed laser beams focused onto a very complex, tiny fusion capsule. The facility is as long as three football fields and 10 stories tall, but the final energy output comes from a tiny sphere you can barely see in the palm of your hand. Does this sound like another of those government exaggerations, maybe similar to Reagan’s “Star Wars” program he announced in 1983? Indeed, achieving fusion ignition is an incredible achievement. Let’s take a look at what happen on that fateful day at NIF.

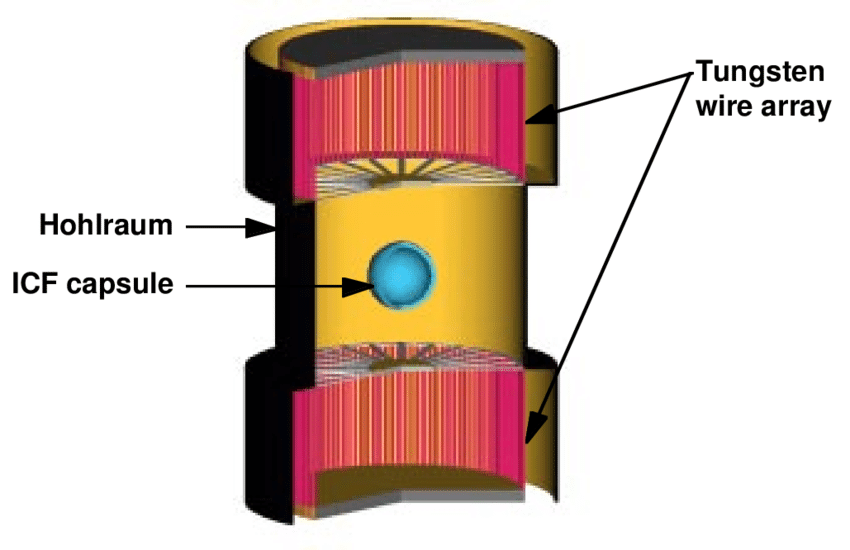

To begin with, there was an incredible amount of stored energy in the capacitors, namely two million joules in each of 192 capacitor banks, to excite the lasers. Next the laser energy entered a 1 centimeter-long cylinder through holes on the ends and heated the inner surface of the tiny cylinder. One of the first technical challenges was that the laser pulse had to be tailored to the right shape over time. The laser light had to be precisely injected into small holes on the ends of the cylinder, and the energy had to be directed and precisely absorbed in a predetermined pattern on the inner wall of the cylinder. Both of these goals were achieved. That exquisitely tailored and perfectly focused energy was absorbed and a fraction of that energy was converted into a hot ionized gas, called a radiating plasma, expanding from the heated cylindrical target’s inner wall.

Inside the cylinder sat a tiny sphere, only 2 millimeters in diameter. Using a microscopic tube, the hollow, flawless, gold-plated diamond shell had been filled with fusion fuel. When the lasers hit the cylinder creating the hot ionized gas, radiation flowed around the sphere and heated its outer surface. This made the outer wall of the sphere explode, causing a violent implosion. A small fraction of that implosion energy compressed to heat a tiny, high density, high-temperature spot at the center of the fuel. This triggers the fusion reaction. The energy released by the fusion reaction heated a fraction of the surrounding compressed fusion fuel releasing more energy.

This was the miraculous achievement of creating a burning fusion fuel using NIF. The compression and heating of the fuel was not the really significant result, the true breakthrough was creating a small hot spot that ignited adjacent cold material. Hot spot ignition is the event that may open the way to the future. There were many tradeoffs of nonlinear variables that had to be adjusted after years of very complex experiments and calculations. And repeating the achievement is still yet to come.

Frankly, before NIF was approved by congress, I had my doubts that such a complex process based on hot spot ignition would ever work, and my skepticism did not please my friends on the NIF team. It is still very hard for me to comprehend the entirety of what happened. The sustained investment of so much money and many years of total dedication in the face of repeated failures is remarkable. The complexity of the concept, and brilliance of the scientific and engineering team, as well as the enormous difficulty of the achievement contributed to this historic event, but it is natural to question the result.

However, based on an extensive array of diagnostic sensors backed up by modeling and simulation of the complex physics, we know it really happened. There were so many incredibly challenging engineering requirements, and so many interdependent very nonlinear physical phenomena that could only be modeled on giant computers. I was skeptical at first, and I am now totally impressed that the NIF team accomplished this remarkable result. Although the phenomenon may be rather hard to duplicate, it happened once, and that makes all of the difference in the long and arduous journey of fusion research. It is just one more of those miracles of engineering and physics!

But what about my attempt at inventing a fictional engineering and science breakthrough in my soon to be published novel, The Dragon’s C.L.A.W. I imagined my story and began writing it several years before this real miracle occurred. In my futuristic technical mystery novel, a low energy nuclear reaction is triggered by an intense relativistic electron beam. The beam triggers a transmutation of the target material into rare earth elements, and the energy output in the form of an electromagnetic pulse is thousands of times greater than the input. No question. This is pure fiction physics, but it draws on some real research I conducted during my career. In 1972 I initiated a fusion program at Sandia National Labs, even applied for and was awarded a patent on an e-beam fusion reactor concept with construction of what I called the Electron Beam Fusion Accelerator. I’ll discuss my fusion research journey in my next post.

`