Seventeen years ago, I was invited to give a presentation to a group of intelligence analysts at the Joint Military Intelligence College. At that time, I was managing the Advanced Concepts Group at Sandia National Labs, and my group was focusing much of our attention on emerging threats. A current issue was what was called “the global war on terrorism.” This war began in Afghanistan in 2001 after the Al-Qaeda attack and continued for 20 years. During that period, it expanded to include Iraq in 2003 with one justification being the belief that Iraq was linked to Al-Qaeda.

Seventeen years ago, I was invited to give a presentation to a group of intelligence analysts at the Joint Military Intelligence College. At that time, I was managing the Advanced Concepts Group at Sandia National Labs, and my group was focusing much of our attention on emerging threats. A current issue was what was called “the global war on terrorism.” This war began in Afghanistan in 2001 after the Al-Qaeda attack and continued for 20 years. During that period, it expanded to include Iraq in 2003 with one justification being the belief that Iraq was linked to Al-Qaeda.

The threat of terrorism was very much a major national security issue, and my presentation attempted to address these issues based on my perceived needs for intelligence analysis. I had been increasingly interested in dealing with current complex challenges, and I studied the literature of systems engineering approach to solving relevant problems. What I learned was that most of my career as an engineer and physicist had been dominated by what were called tame problems, and the national security issues of the time were best described as wicked problems that would be long in duration.

I was convinced that the current military issues were best described by a timeline beginning with a long period of increasing threat, and short period of conflict, and a much longer post conflict period of managing the threat. I thought the key to success of this challenge would be in the hands of intelligence analysts that knew how to deal with wicked not tame problems.

Tame problems had been the focus of my training and career, and are the typical challenge for analysts, engineers, and convergent thinkers. Such problems have a well-defined problem statement. For example, a tame problem is figuring out how to build a bridge. A wicked problem includes planning for the bridge, obtaining permission from the community and elected officials to build it, acquiring funding and scheduling, and working with the various individuals and agencies required to build that bridge. The bridge builders know what, where, and how to proceed with a well-defined end point of the task. They can learn from the records of other similar bridges already built and can easily try out various paper designs and choose the one most appropriate approach. They have an orderly approach to analysis, design, and implementation, but do not have the divergent thinking approach that is actually needed to complete all of the tasks involved in building the bridge.

The typical tame approach can lead to disaster if the problem is really wicked. If the problem is defined incompletely, prematurely, or influenced by desperation, ambition, fear, greed, hatred, or other emotions. Being driven to a hurried solution can lead to oversimplified solution options and an early and false belief that the problem is solved. The different perspectives, backgrounds organizations, and prejudices can lead to escalating confusion, conflicts, and paralysis.

A symptom of a wicked problem that is treated as tame is when the leader says, “Let’s get organized, put the right person in charge, get on with the solution, and get it done.”

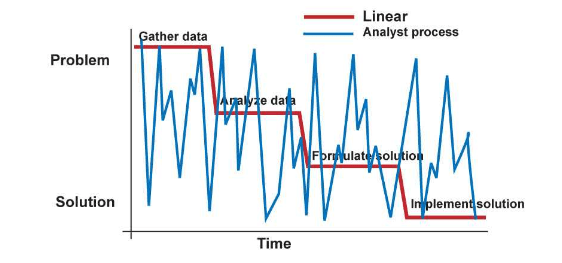

The tame problem approach is a satisfying and coherent method of increasing knowledge. Wicked problem solving, on the other hand, can often be characterized by frustrating alternating periods of euphoria and utter depression. So, are wicked problems just another worthless activity that is in the end a hopeless mess?

Well, maybe, but if you know the problem is truly wicked, a wicked engineering analyst can make real progress by spending a great deal of time and effort to comprehensively formulate the approach as a nonlinear spiral instead of a ladder of subsequent steps. The key is also to share the complexity with a group of creative thinkers and communicators that have a diversity of views. It’s important to share ideas frequently as the context of system issues changes and avoiding a focus on the detailed piece of the problems. Since premature belief in success will turn out to be the devil preventing group productive cooperation, the participants need to trust each other as the game changes.

I concluded that without active counterterrorism intervention, the level of terrorist violence will be low until a triggering threshold is passed, and, at some point, conflict will demand increased security emphasis. If successful, counterterrorism actions can be taken that will lead to a cessation of combat operations. This period will be followed by a long period of stabilization and reconstruction. During the active combat period, the adversary may apply such irregular methods as assassination of leaders; hostage taking; cyber, bio chem, and infrastructure attack. The adversary may also introduce social and psychological methods such as induced chaos, exponential migration, financial attack, and race wars. The symptom of terrorist success would be a disruption of societal stability and stimulation of self-destructive behaviors.

A strength of the wicked engineering group could be the application of ubiquitous information technology, but in the hands of the terrorist, could also accelerate instabilities, so it will be necessary to take advantage of advances in complex computer modeling and simulation as well as the application of neuroscience to enhance cognition and group problem solving.

By gaining a neuro advantage over the adversary, methods of deterrence and dissuasion will become apparent. The advances in the neuro science spectrum can enhance the psychological armor, accelerate learning, cognition, and memory. Use of such methods applied against the terrorist can create confusion, fear, and loss of understanding of the rapidly changing environment. The adversary’s use of such psychological and information warfighting tools can lead to our early failure in dealing with the threat. The positive and negative implications must be understood.

At the time of my presentation, I believed that neuroscience advances in the hands of the adversary (which won’t have the same legal and moral constraints that we have) would have an important impact on the outcome. I also believed that the challenge of dealing with terrorism was open ended and there would likely never be a last move in this contest, so the happy ending to the story was not obvious.

My new novel, The Dragon’s C.L.A.W., also tackles a wicked problem. The protagonist realizes that his breakthrough invention, which has the ability to transform the world by providing clean, affordable, unlimited energy, can also be used to create a deadly weapon. I called upon my understanding of how to wrestle with wicked problems as I described how the character dealt with the conflict the dual nature of his work. Wondering how he resolves the problem? You’ll have to read the book!

Have you ever dealt with a wicked problem? How did you approach it? Did you resolve it? Comment below.