What if Trump had succeeded in overthrowing the election?

Former President Donald Trump apparently was totally dedicated to being declared the winner of the 2020 election, and he might have been successful if he had been able to persuade a number of members of our elected and appointed government organizations to go along with his plan. It is conceivable that the result would have been a rejection of the election results and the emergence of an unworkable form of government leading to political, social and economic chaos. The extreme forces on the liberal and conservative sides of the social and political spectrum might have launched a power struggle that could also involve military forces to enforce some sort of an interim government approach. It seems rather hard to believe that a world economic and military power with the ability to launch a nuclear war could totally lose control of its fundamental decision making and management abilities, but this would not have been the first time this has happened, and it would be useful to consider a little history lesson.

On Aug. 20, 1991, the Soviet government was preparing to sign a treaty that would have changed the relationship between the central government and the republics of the Soviet Union. The force behind this agreement was Mikhail Gorbachev, the man in charge, who along with a group of loyal followers wanted to change just about everything. He was in the process of creating a new form of government that he had been working on since 1985, and his goal was an entirely new economic and military approach.

Gorbachev envisioned a non-militaristic, non-autocratic, and globalistic liberal form of government driven by an entrepreneurial spirit like most of the rest of the world. He was convinced that the old Communist approach was doomed to failure. At the same time, he harbored the concept that he could preserve Communism in some form, but he was not too clear on that. He knew that the constant drain of funds to support all of the poor and gradually getting more poor republics would lead to inevitable failure of the government, and he was prepared to turn the dependent client states loose to fend for themselves. He had tried all sorts of approaches to turning around his country and one of his schemes was to end rampant alcoholism without considering that it was a major source of income to run the government, and this decision just added to the increasing economic woes.

The Soviet leader also was convinced that the military industrial complex was a major cause of economic disaster and he did everything he could do to derail attempts to spend increasing funds on defense in general and space weapons in particular. His goal was not only conventional disarmament, but also the elimination of all nuclear weapons. Strangely enough, there was at least one other person in the world that agreed with the nuclear part of his plan, and that was President Reagan, but that is a different story, so back to the overthrow.

A group of eight high-level Soviet officials put together a plan to take over the government and put a stop to any treaty that would lead to the end of the Soviet Union. They waited until it was almost too late and they did not really think through how exactly they would manage to run their new government. Nevertheless, with only two days to go, five of them showed up at Gorbachev’s vacation home in Crimea. Their plan was to convince him to sign an emergency declaration that put would put them in charge of the government.

One of the most important participants in this coup was Oleg Baklanov, the head of the military industrial complex and a man dedicated to restoring the global space leadership that they had demonstrated beginning with Sputknik in 1957. He believed that the Soviets had managed to let the Americans take over with the latest move being Reagan’s SDI that he believed could easily be handled if he were allowed to get on with running the show. He was convinced that he knew how to win this latest form of technical competition and his approach was to develop and deploy their own death star, called Polyus, which would control space. The only issue was that Polyus had crashed into the Pacific after its launch in 1987, but only because of a minor software glitch, and Baklanov was not ready to give up on his engineer’s technology approach to problem-solving.

Baklanov had a running battle with Gorbachev and tried to persuade Gorbachev that he really had a better idea based on the superior scientific and engineering capabilities of the military R&D branches of the government. After many attempts to get his way, he concluded that Gorbachev cared little and barely understood the miracles of Soviet technology and was driven by his own political philosophy. Baklanov thought at least half of the military technical advantages were already devoted to the non-military needs and were best managed by stepping up military spending rather than somehow turning over the economy to a free and non-governmental form of big business.

When the coup plotters confronted Gorbachev, Baklanov later claimed in his oral history that Gorbachev “was dressed in a sweater although it was hot outside … to emphasize that he really was sick … became rather emotional and I saw a dull man thinking in a dull way about himself, rather than the matter at hand … and said he would sign the treaty even if they cut off my legs.”

The plotters left without any agreement and headed back to Moscow to “make arrangements” including getting Boris Yeltsin to go along with their plan, but that was not to be. When Gorbachev returned to Moscow few days later still wearing that same sweater, he found that the coup plotters had ordered tanks and military to take over and enforce their coup. Yeltsin then called on the public to strike and protest the coup. Yeltsin climbed on a tank, and with a megaphone and demanded the coup be defeated, and when the military refused to fire on the crowds, the coup was essentially over in three days and the plotters were arrested. Some spent time in prison but were released after an amnesty was declared in 1994. Gorbachev’s chief military adviser who had signed up with the coup committed suicide when it failed. An active coup plotter, Boris Pugo, along with his wife also took their own lives.

Gorbachev agreed with Yeltsin to abolish the Communist party, and in December the hammer and sickle flag was lowered, but then what? What was the outcome of a new freedom with lots of influence from the West? It is reported that without the law and order of the old government, the mafia that had been created when Gorbachev got rid of vodka took over and a new approach to big business emerged with oligarchs in charge.

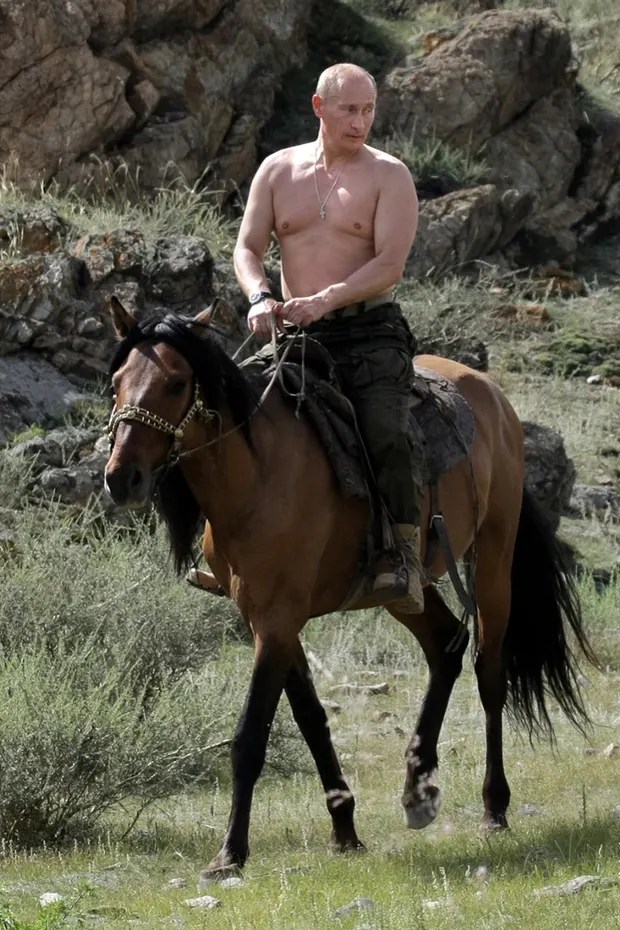

Violent uprisings were not uncommon, and the government went into a multiyear economic and social collapse. Then Putin, with his KGB backing, rode shirtless on his horse to the rescue in 1999 by restoring law and order and increasing autocratic control. Putin believed that the collapse of the Soviet Union was “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.” His attempt to regain control of the Soviet republics has resulted in today’s rapidly evolving war in the Ukraine, and a renewal of the conflict between the West and Russia with consequences yet to be determined.

So what did I conclude from all of this history story? Certainly we are not Russia, and we have resilient institutions that work well under stress. Not surprisingly, I believe an orderly transition of power that reflects the will of the governed is a rather good idea. When the rule of law and reasonable people make the transition decisions in a cooperative manner, it is better than a disorderly overthrow of the government. Had it happened here, we might have seen the lessons of Soviet history revisited on our own shores.

story about the genius inventor Garin described a weapon with pinpoint, but still incredibly destructive, capability. This prophetic novel not only predated by decades the invention of the laser, but it also quoted Garin’s detractors as claiming, “This invention smells of higher politics.”

story about the genius inventor Garin described a weapon with pinpoint, but still incredibly destructive, capability. This prophetic novel not only predated by decades the invention of the laser, but it also quoted Garin’s detractors as claiming, “This invention smells of higher politics.” launch vehicle Energia. The payload for the launch was the 80 ton Polyus experiment dedicated to the development of a space control laser weapon. Polyus was a giant risk that was characteristic of the Soviet experimental technology philosophy of try it, learn from failures, fix it and try again. The huge gamble had been in the works as a multiyear high power laser program that was already underway but became a crash program in response to Reagan’s SDI initiative. Instead of trying to compete with their own space-based missile defense program, they decided that laser-based space control would be the most logical path to defeat the SDI. Gorbachev knew that even a minimally successful deployment and test would lead to a space weapon race with the United States. He knew that his failing economy and inferior computer and electronics technology would certainly just accelerate the Soviet path to failure. Fortunately Polyus failed to orbit because of a software problem, and a real star war was avoided.

launch vehicle Energia. The payload for the launch was the 80 ton Polyus experiment dedicated to the development of a space control laser weapon. Polyus was a giant risk that was characteristic of the Soviet experimental technology philosophy of try it, learn from failures, fix it and try again. The huge gamble had been in the works as a multiyear high power laser program that was already underway but became a crash program in response to Reagan’s SDI initiative. Instead of trying to compete with their own space-based missile defense program, they decided that laser-based space control would be the most logical path to defeat the SDI. Gorbachev knew that even a minimally successful deployment and test would lead to a space weapon race with the United States. He knew that his failing economy and inferior computer and electronics technology would certainly just accelerate the Soviet path to failure. Fortunately Polyus failed to orbit because of a software problem, and a real star war was avoided.