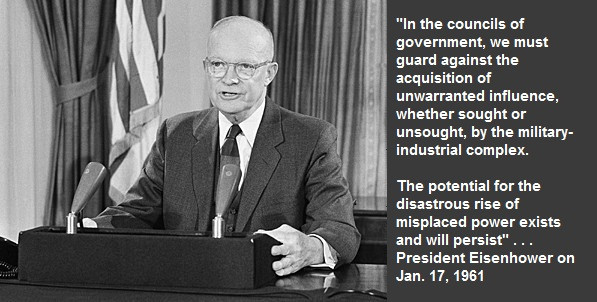

The purpose of this blog post is to consider the evolution of military technology and explore what has happened in the last 80 years, and what might the future hold. Before World War II, technology was rather primitive by today’s standards, but it was on the verge of dramatic changes driven by the necessities of the war. Nuclear weapons, long distance rockets, and computers were about to appear, and global conflict was the catalyst to create dramatic advances. But then the deployment of new weapons followed a slower schedule with decreased military requirements and with funding competition from non-military investments. Even though technology budgets were somewhat restrained, Eisenhower still warned against “the establishment of a ‘military industrial complex,’” and he worried about the size of the defense industry that had grown in the 1950s,

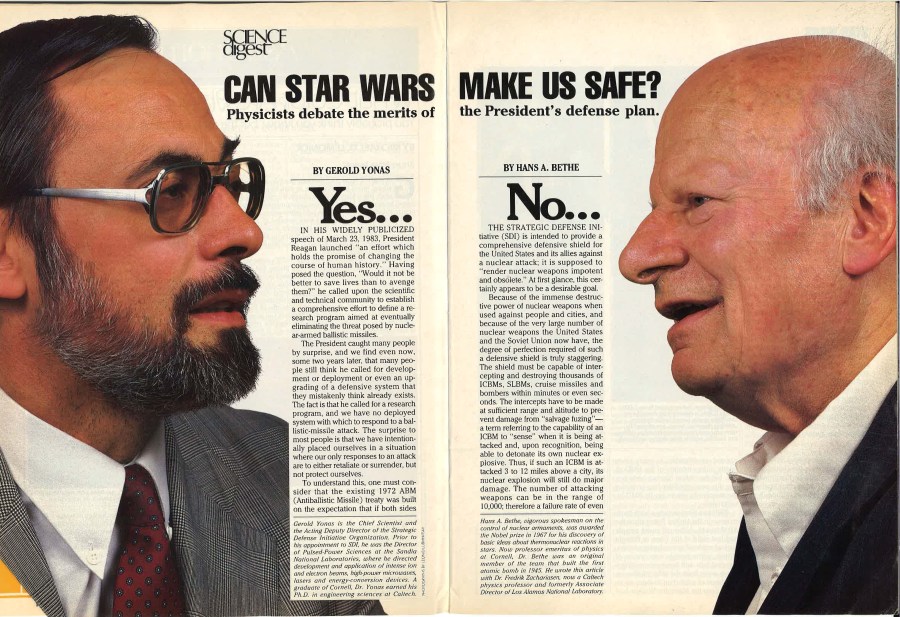

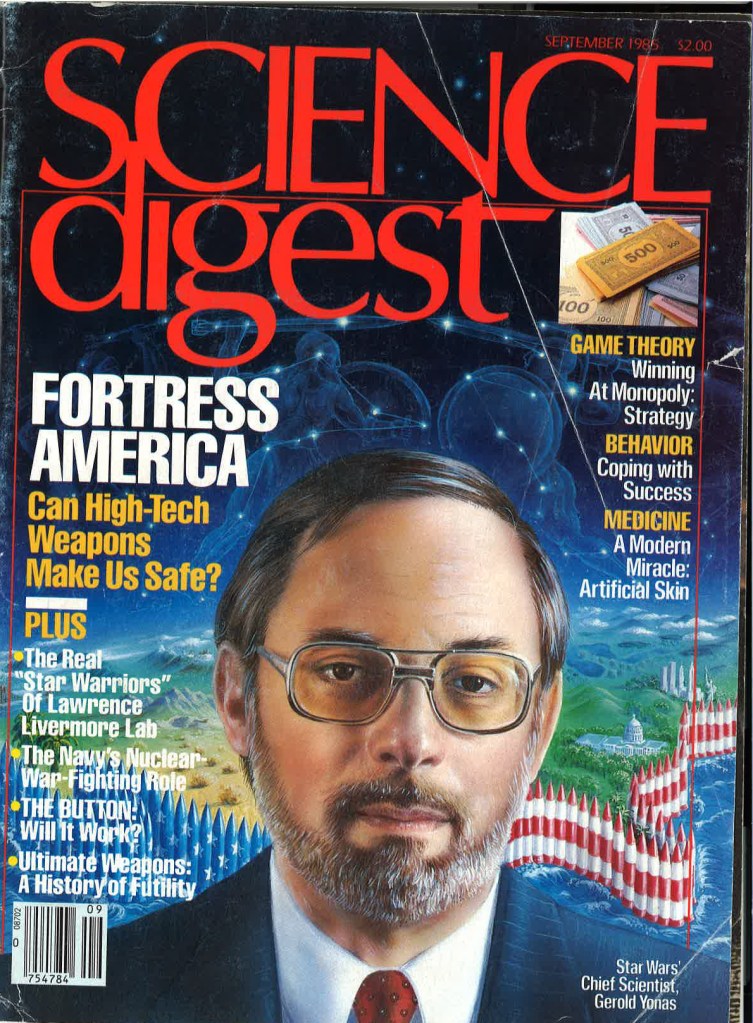

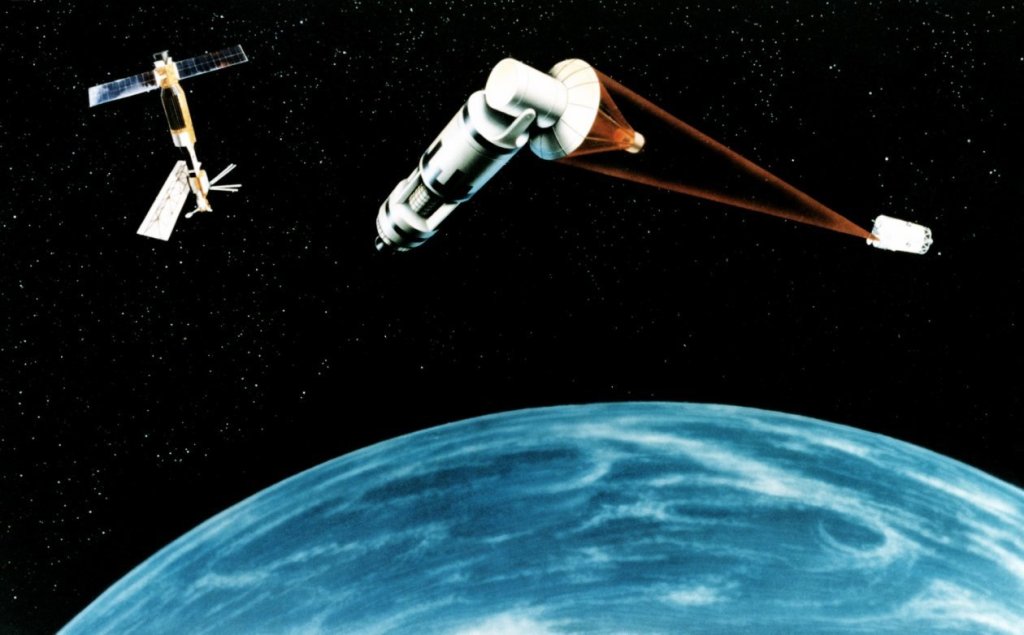

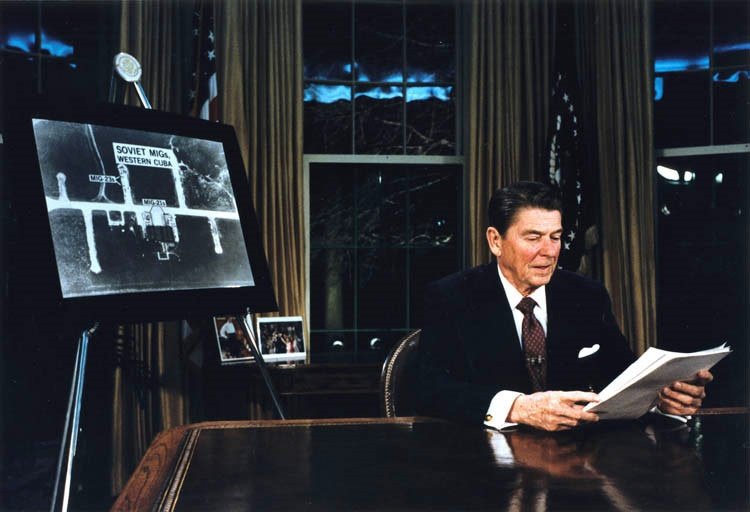

Within a few decades, however, new technologies began to appear driven by the threats emerging from the Cold War and with the emergence of new weapon concepts, new aircraft, advanced materials, directed energy weapons, and ever-increasing speed and memory storage of computers. By the 1980s, there were lots of new weapons investments: deployment of intercontinental ballistic missiles carrying multiple warheads, a reuseable space shuttle, directed nuclear weapons, particle beam weapons, high power chemical lasers, and space-based sensors. Many enthusiastic aerospace engineers in the United States and the Soviet Union prowled the halls of their military organizations marketing new missiles as well as space and laser weapons to no avail. In the United States, budgets were tight, and national debt was feared more than the Soviet Union. But then, the announcement by Reagan in 1983 of his goal to eliminate the threat from nuclear weapons rapidly accelerated a new nationwide technology development program that started to receive slowly increasing funding in 1985.

Technology advocates soon had some political and technical setbacks. Congress passed the 1985 Balanced Budget Act, and the Pentagon faced many competing investments. Even though the Pentagon had been investing in many new concepts such as space-based lasers, Congress was not enthusiastic about giant programs. Even with the likely suspects, such as Edward Teller, who was selling his nuclear pumped x-ray lasers, the majority of the scientific community was skeptical. Then the Shuttle Challenger that the SDI program planned to use for early deployment of space weapons exploded shortly after liftoff. Nevertheless, many new programs were getting started slowly and Reagan was reelected with support for continuing emphasis on increasing defense budgets, The U.S. technology advances were just getting started but with very slow advances in high power lasers, but with real progress, primarily in the evolution of ground launched defensive missile systems, when the Soviet Union began to fall apart.

One year later, they signed an arms control agreement to ban intermediate range nuclear missiles that represented a serious strategic stability problem because of the short flight times of such missiles to and from Europe. The treaty remained in force for 10 years until Russia violated the treaty. Recently, the technology competition heated up again when Russia attacked Ukraine with such a missile carrying six non-nuclear warheads, each carrying six submunitions and fully capable of delivering nuclear weapons and attacking Europe in minutes. Now the need for missile defense has been made obvious to even the most dedicated advocates of arms control. And even more troublesome is the fact that the Russians have a well-developed capability to deploy methods, called penetration aids, to defeat any ground-based missile defense.

In April, 1986, a reactor at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant exploded contaminating Europe with radioactive material. That event was bad enough, but for the Soviet Union, the bad news just got worse and then even worse. They were already in a rather bad mood with their crumbling economy and had to deal with our active secret programs to blow up their pipelines and mess with their computers and software. At the same time, Gorbachev feared that with the United States increasing funding for our missile defense research, a space arms race would be the final blow in his attempts to save the Soviet economy. Then one of their ballistic missiles carrying submarines sank, and a Russian cruise ship carrying dignitaries collided in clear weather with a freighter in the Black Sea.

Gorbachev’s military experts convinced him that the United States would deploy space weapons in only a few years. Meanwhile, his own military industrial complex was preparing their own giant space laser for initial deployment the next year. As it turned out, there were many feverish aerospace engineers in both countries ready to be rewarded with unlimited funds. They were disappointed when not only was the technology not ready, but Reagan and Gorbachev decided to get along.

I believe that strategic political environment and technology have evolved to the point that we need to reconsider one of our old ideas for defense against nuclear tipped ballistic missiles based on lasers in space. The most advanced laser weapon system at that time was called Zenith Star and Reagan thought we were only a few years from a real defense. In reality, the technology fixes involved were not even close. The laser was one problem, but our computers for battle management were inadequate and the shuttle was much too expensive for a giant space deployment. Today times have changed, and so has technology.

Twenty years ago, practical high-power lasers were just concepts on viewgraphs, but DARPA formulated an ambitious program to create multiple combined fiber lasers with “tens of kilowatts and capable to be scaled to hundreds of kilowatts. A 500 kilowatt laser will exist soon and we are on the way to 1000 kilowatts. Not only are electrically pumped fiber lasers real today, but they have been moved from the research labs and are being used in manufacturing operations. They are also being deployed on ground and sea vehicles to intercept slow missiles and swarms of drones. Those are only some of the advances that indicate we need to take another look at missile defense using high power lasers.

Back in the 1980s, in spite of Reagan’s enthusiasm, the technology for large scale deployment of weapons into space was not a realistic possibility. Even if we had not suffered the loss of the Shuttle, we had no way to afford deployment with the cost of lift close to tens of thousands of dollars per pound. But now Space X is realistically offering lift at thousands of dollars per pound, and predicting 100 times less if everything but the rocket fuel is reuseable. In addition, Space X has launched thousands of Starlink satellites and changed the way people work and play. Elon Musk has certainly revolutionized access to space, and the entire missile defense system concept needs to be rethought without restrictions on deployment cost.

But what about the problem I thought would be the real show stopper, and that was the trusted computer hardware and software needed to allow the decision maker to instantly respond to a warning? When I worked at Sandia National Labs, our fastest computer had a computational speed of one trillion operations per second. Today the fastest computers are one million times faster, and the practical applications of modern computers and the decision support software is so real that modern industry is investing in technology that has driven the leading supplier to become more than a 3 trillion-dollar capitalization corporation.

So now what? With many extremely impressive advances in technology, I believe now is the time to ask again if Ronald Reagan’s dream of March 23, 1983 can become a reality. And as usual, even if the technology is enormously successful, there will be unintended strategic consequences that should be carefully explored.