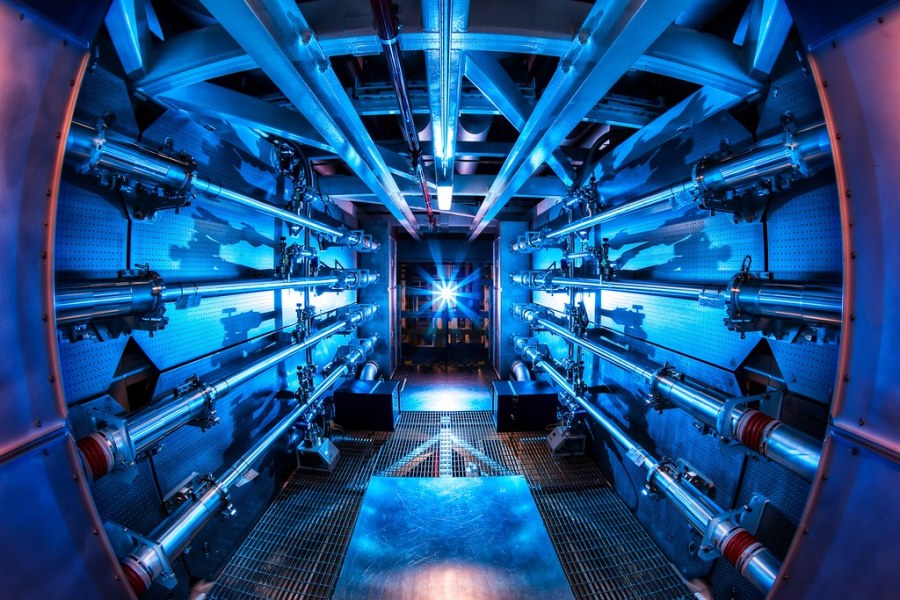

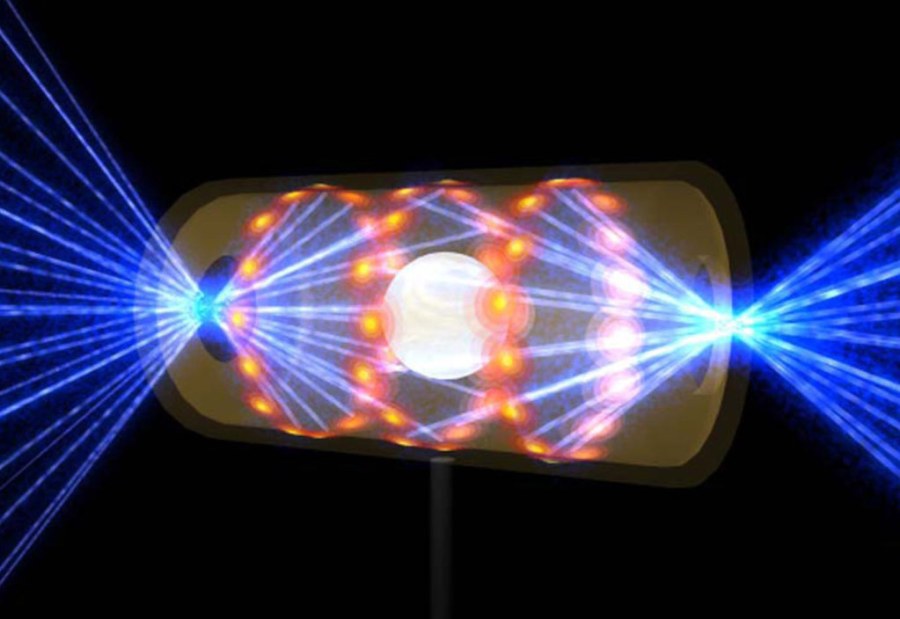

It is widely known that one promising way to create fusion in the laboratory is called inertial confinement fusion (ICF). It is based on the concept of spherically imploding, compressing and thus heating thermonuclear fuel. Indeed, the recent laser fusion breakthrough at the Livermore National Laboratories demonstrated efficient hot spot ignition and self-heating of cold fuel. There were many complex requirements in this outstanding technical achievement, but probably the most significant was spherically symmetric implosion of the fusion capsule. This was accomplished not by directing the 192 ultra high power laser beams at the target, but instead heating the inner walls of the tiny chamber containing the fusion pellet, and using the radiation trapped in the chamber to symmetrically heat the pellet. This chamber is called a hohlraum, which is a German word for a hollow volume of cavity in a structure. When I first became interested in fusion research, I had no notion of this vital ICF concept. In fact, just revealing the very idea of heating the target with indirect radiation rather than direct heating by the laser beams would have resulted in a severe penalty, or even jail time. Today, the hohlraum concept is totally unclassified.

In 1967, when I became interested in fusion, I knew that the physics worked well in the sun and in H bombs, but I knew little else about the subject. I was attracted to work for a small startup company that was pioneering work on pulsed power technology. This was a very new field of electro technology dedicated to creating machines that generated very short pulses of electric power levels of 1 trillion watts (TW). The purpose of these machines was to create laboratory sources of pulsed radiation to test the vulnerability of reentry electronics faced with an H bomb tipped missile defense. The issue was to determine the exact vulnerability of the electronics to such a pulse. I was drawn to that company, Physics International, not because of the question of missile electronics vulnerability, but because the founders of the company had previously been H bomb development leaders at the Lawrence Livermore Lab, and they convinced me that such machines could be used to make a tiny H bomb explosion in the lab using the new pulsed power technology.

On a warm and clear day in June 1971, at the University of Wisconsin student union, I met with a well-known plasma physics theorist, Lyonid Rudakov, from the Kurchatov Institute in Moscow. He and I sat there in the sun like old friends drinking coffee and chatting about the subject of creating fusion with electron beams. We were both in our thirties, and had just met and learned that we had a common interest in using high intensity electron beams to create fusion. I knew exactly what I could and could not discuss, and I had no idea about the connections of Rudakov to any Soviet secret information. Rudakov was very outgoing and obviously comfortable with people he did not know well, and from the first I recognized that we had one thing in common. We both were in the business of marketing our ideas on fusion to get funding.

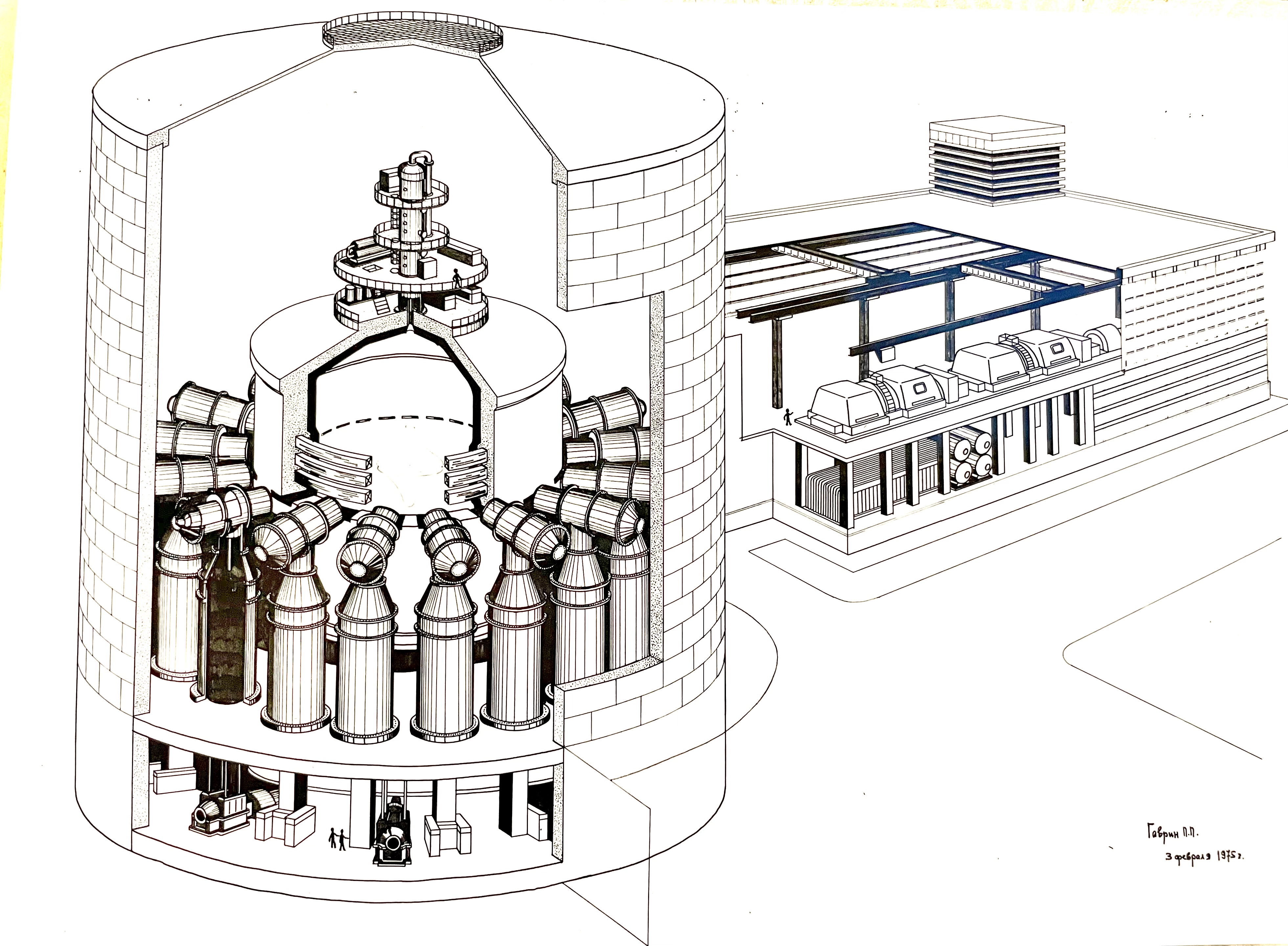

As we talked, we shared a fantasy of building giant pulsed power machines, maybe hundreds of times bigger than anything in existence, and focusing relativistic electron beams onto BB size pellets. Rudakov already had an established program at a major Soviet research laboratory, and I, with no continuing government program support, was mostly concentrating on getting funding every year for my small program dedicated to simulation of nuclear weapons effects. I knew that I would never get very far with my vision unless I established a major program in a national laboratory.

One year later, I found that there were others who shared my fantasy, and I moved to Sandia National Labs in Albuquerque. After I received my clearance, the first question I asked was about the physics of the H bomb. I learned that the highly protected secret was the use of a fission device to produce radiation and it was the radiation trapped in a hohlraum that drove an implosion and fusion ignition. I thought that electrons, if they could be focused highly enough, could be used instead of radiation. I invented an imaginative, if not realistic, program based on my published very early experimental work with electron beam focusing but still with no real quantitative knowledge of the power level that would be needed for fusion ignition.

Rudakov had the backing of the most influential Soviet scientific/political engineer but I was unknown in the scientific community. I had a vision and motivation based on my experience at my first job after I completed my Ph.D. at Caltech. I received my Ph.D. in Engineering Science and Physics in 1967 and continued on at the Jet Propulsion Lab where I had done my research on magneto fluid dynamics since 1962. The lab had failed six times to take close-up photos of the surface of the moon and was faced with a major transition. The question that they were trying to resolve was if the proposed moon lander would sink into deep dust. Unfortunately their payload, called Ranger, either was destroyed during the launch or crash landed time after time with no data. Although the lab went on to success, they had decided its job was exploring space and not basic research. My small fluid physics group was disbanded and they gave me the opportunity to move on, and that resulted in my first job as a new Ph.D. Married, with a 1-year-old daughter, I was highly motivated to succeed.

When I got to Sandia I found out that since the U.S. had agreed with the Soviet Union to prohibit anti-ballistic missiles, funding for development of nuclear weapons and lab funding had decreased. There would be a 10% reduction in force. I was a first level manager, but my quota for the layoff was to fire one person, and I was given freedom, as my boss said, “Go out for a pass.” The misfortunate layoff had a silver lining since I had the support to do something Sandia was not too experienced with, namely lobbying the Congress for funding.

After spending a lot of time getting to know our representatives from New Mexico and prowling the halls of Congress, I managed to influence Senator Joseph Montoya, who was primarily known for his somewhat inadequate but televised questions when he served on the Senate Watergate Committee. He was not a technically educated person, but he was sympathetic and told me he always rooted for the underdog. When he learned we were competing with a powerful lab in California that already had funding for laser fusion, he agreed to try to get minimal startup funding for my program. I also had support from the fusion research organization at the AEC because they also were happy to create competition with the laser program managed by the weapons division. This caused a negative reaction from the weapons program to my dealing with the “wrong organization.” I agreed to accept weapons program funding that was far more generous as long as I had no more dealings with those “research guys.”

Our plans were not advertised publicly until the July 1973 European Conference on Controlled Fusion and Plasma Physics in Moscow. At that meeting I together with my Sandia colleagues, who were as new to the game as I was, claimed that very high current electron beams could be self magnetically stopped in a thin shell driving the implosion, and could achieve fusion breakeven with “extensions of present day technology.” Rudakov, together with a well-known Soviet mathematician from the Institute of Applied Mathematics, carried out detailed calculation of the needed power for 1000 TW and they included the vital concept of self-heating of the fuel after ignition as demonstrated last year on NIF “only” 50 years later with 1000 times more energy than they had originally calculated in 1972.

After the meeting in Moscow, Rudakov and I became technical colleagues with reciprocal visits, and we continued to share information as both of us advertised the start of major competitive programs. Sandia began construction of prototype devices at power levels of a few TW, and advertised the development of a machine in the 100 TW class, but both of us were competing with the rapidly growing programs in the U.S. and Soviet Union that had much more funding for the use of high power lasers. I knew that electron beams created with low cost and efficient pulsed electrical power would be far more energetic than lasers. I guessed that even if millions of joules would be needed for ignition, it would be a more reasonable approach than the very expensive and inefficient lasers.

The LLNL results were achieved using the NIF laser to deliver 2 million joules to heat the walls of a hohlraum containing the fuel pellet and using the symmetric flow of energy in the hohlraum to heat the outer surface of the pellet. The physics of the hohlraum is based on the fact that the heated cavity walls come into thermal equilibrium with the energy in the cavity, delivering energy symmetrically to the fuel capsule. The reason for the closely held secret in the 70s was the idea of using the radiation in a hohlraum to implode and heat a fusion capsule. This is called the Teller/Ulam principle, the secret of the H bomb. The H bomb concept relied on a two stage process with the radiation from a fission explosion to heat and compress a fusion device, but that was very secret in the 70s. The reason for the high level of secrecy was not because we were afraid the Soviets would get the secret, which we knew they had, but for fear others would catch on and that would lead to proliferation of hydrogen bomb technology. So both programs progressed, but Rudakov knew something he was not sharing. In 1976, he announced with no details that his lab had produced the first fusion reaction using electron beams. The March 1976 “New York Times” reported, “Russians report fusion using electron beams,” but with no details. There is more to this story, to be continued in my next blog post.