The new actor on the Soviet scene in 1986 was Mikhail Gorbachev. After the deaths of three Soviet leaders since 1982, Gorbachev became the new head of the Soviet Union in 1985. He immediately found that he was faced with managing total economic collapse and political chaos in competition with the most powerful Soviet force, their own military industrial complex. He seemed to be an idealist committed to open communication and restructuring and faced a never-ending collection of problems. He pressed on nevertheless with enthusiasm, optimism and charm.

One of Gorbachev’s first initiatives was to wage war against alcohol, which he believed was one of the reasons for the failure of the Soviet economy, but he only managed to cut off a major source of government income from the Soviet vodka monopoly. The alcohol kept coming, however, and the illegal vodka income then went instead to their own version of the Mafia. Soviet historian Vladimir Zubock described these events writing, “The Soviet socialist empire, perhaps the strangest empire in modern history committed suicide.”

Well, maybe Soviet suicide is a bit of an overstatement, but there really were enough serious troubles facing Gorbachev to cause at least a feeling of overwhelming depression. In April, the Chernobyl reactor disaster, the worst nuclear power plant accident in history, causing more than 300,000 people to be resettled, threw Gorbachev into a desperate lack of trust in Soviet technology. And there is more to this sad story. In September, the pride of the limited Soviet fleet of luxury cruise ships collided with a freighter in clear weather and hundreds of wealthy Soviet citizens died leading to a nation overcome by “pessimism and foreboding.”

Some people believe the superstition that bad things come in threes. The third blow struck in 1986 and it may have been the worst. The event was the sinking of a Soviet nuclear submarine, but that was not the first time that such a disaster happened. In 1968, the K129 nuclear missile carrying submarine sank to a depth of 5000 meters in the Pacific 2700 kilometers from Hawaii. After the Soviets failed to locate it, a U.S. ship found it, and an enormous, technically fantastic and very secret CIA program called Azorian tried to lift it, but it broke apart on the way up and it was never revealed publicly what we recovered. When remembering the history, it is easy to confuse 1968 with 1986 and K129 with K219, but let’s try to get it straight.

In October 1986, the K219, one of their ballistic missile submarine with 34 nuclear warheads, sank within 1000 kilometers of Bermuda, but this time there was no problem finding it since a trailing U.S. submarine was watching the disaster. At first, the Soviets blamed the disaster on a collision with our submarine Augusta, and I can imagine that Gorbachev, who was actively engaged in negotiating with Reagan to put a stop to any more high-tech competition with the U.S., was stunned when he got the message that the sub was on fire. I imagine he felt a sense of desperation and had given up on competing with the United States. In a bit of additional mystery, a Soviet deep water research probe found later that the sub was “sitting upright on the ocean floor with empty missile tubes dangling open.”

Gorbachev was in no mood to compete and was even prepared to give up all of the Soviet nuclear weapons. His only condition for mutual abolition of nukes was our agreement to “10 years of research in the laboratories within the treaty” and he made it clear ‘it’s laboratory or goodbye.” I think he did not want the Soviet “death star” to be launched and he knew he could not put a stop to his own aerospace industry enthusiasts creating a new weapons race unless we first agreed to keep our program out of space. So my argument not accepted by the real experts, is that he was more worried about the SDIsky than the SDI.

Maybe he thought he could turn around the course of economic and technological history in 10 years, but Reagan would not go along, even though he hated nukes. The problem was that he believed we were ready and able to deploy defenses, which of course was false. In my opinion, the Soviet Union was on the way out even without our “help” because of its moral decay and mismanaged economic and political institutions. A nuclear agreement might have helped us deal with the global spread of nuclear weapons and maybe even contributed to an economic turnaround for the failing Soviets. Instead, the world still has more than enough nukes to go around, including North Korea. In addition, there is the growing capability of Iranian program, even without their “top nuclear scientist.” Well, some things don’t change and space-based lasers are still far off in the future.

But maybe there are lessons to be learned from the events of 2020 and we won’t have to make the Soviet mistakes. The world has seen plenty of surprising and horrible recent catastrophes, but there is reason. I had hoped that our new United States president would not be faced with the same sort of economic, political and social mess that confronted Gorbachev only 34 years ago. Maybe, I thought, we can solve some of our own economic and public health problems, and figure out a way to just “learn to get along” both within our borders and with our adversaries in other countries. That is, before Jan. 6, 2021, in the words of FDR, “a day which will live in infamy” that has exposed our own socio-political frailty.

My view was even becoming optimistic after the presidential election, until I realized that many of the governance problems that Gorbachev faced, are looming in our own future. Possibly we cannot avoid the seemingly inevitable repeat of wide spread self-destructive decision making of nations under stress. It seems that a nation cannot easily avoid reacting poorly to its history of traumatic events, but I hope we have learned our lessons.

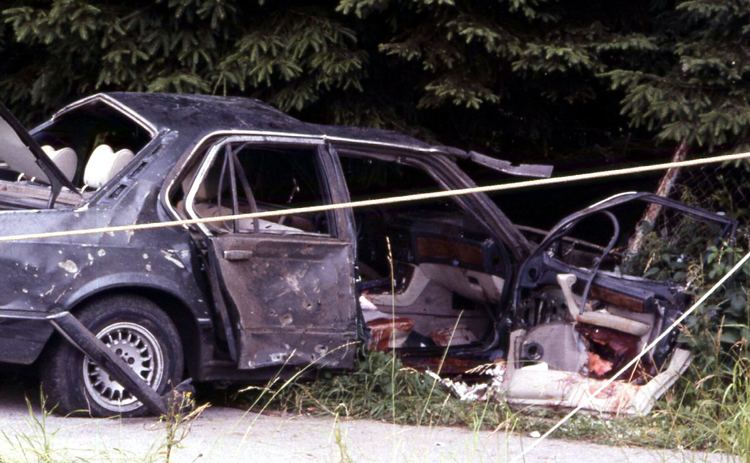

Oh, one more thing about history. And that is what happened a few months before Beckurts was murdered. He and I had a very nice meeting to talk about German involvement in the SDI. My goal was to get him to agree to a contract that would support our program. Over lunch in an elegant German restaurant, he explained to me in no uncertain terms that his company did not support the SDI and had no intention of participating.

“High-tech research director and driver slain by bomb.” Sound familiar? You probably think it just happened in Iran. Actually this happened in Bonn, and the headline was from the July 10, 1986, New York Times. You probably confused it with the very similar November 2020 New York Times headline that read, “Iran’s top nuclear scientist killed in ambush.” So, history repeats itself, but we really do not learn that much from history since we tend to forget. Let’s try to remember.

“High-tech research director and driver slain by bomb.” Sound familiar? You probably think it just happened in Iran. Actually this happened in Bonn, and the headline was from the July 10, 1986, New York Times. You probably confused it with the very similar November 2020 New York Times headline that read, “Iran’s top nuclear scientist killed in ambush.” So, history repeats itself, but we really do not learn that much from history since we tend to forget. Let’s try to remember.