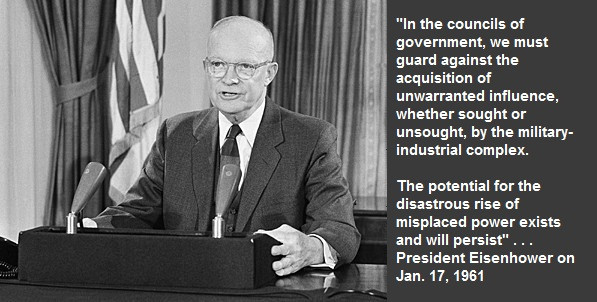

Last year Donald Trump announced that “we must be able to defend our homeland, our allies, and our military assets around the world from the threat of hypersonic missiles, no matter where they are launched from.” After his election, he called for a program labeled the Golden Dome, and he requested a plan with no limit on cost to achieve his goal. This brought back many memories from 40 years ago.

Although I had been involved and frustrated for many years with the rather slowly advancing R&D related to space-based missile defense, I became intrigued by new ideas after I had a lunch conversation with the brilliant and creative physicist Freeman Dyson. I had become convinced that the tactics and technology needed to counter a massive missile attack would always fail. I was sure that the offense would always have the advantage. Dyson introduced to me a more interesting way of looking at this complex issue. Dyson told me about his concept of a quest that would “allow us to protect our national interests without committing us to threaten the wholesale massacre of innocent people.” He argued on moral grounds for “a defensive world as our long-range objective … and the objective will sooner or later be found, whether the means are treaties and doctrines or radars and lasers.”

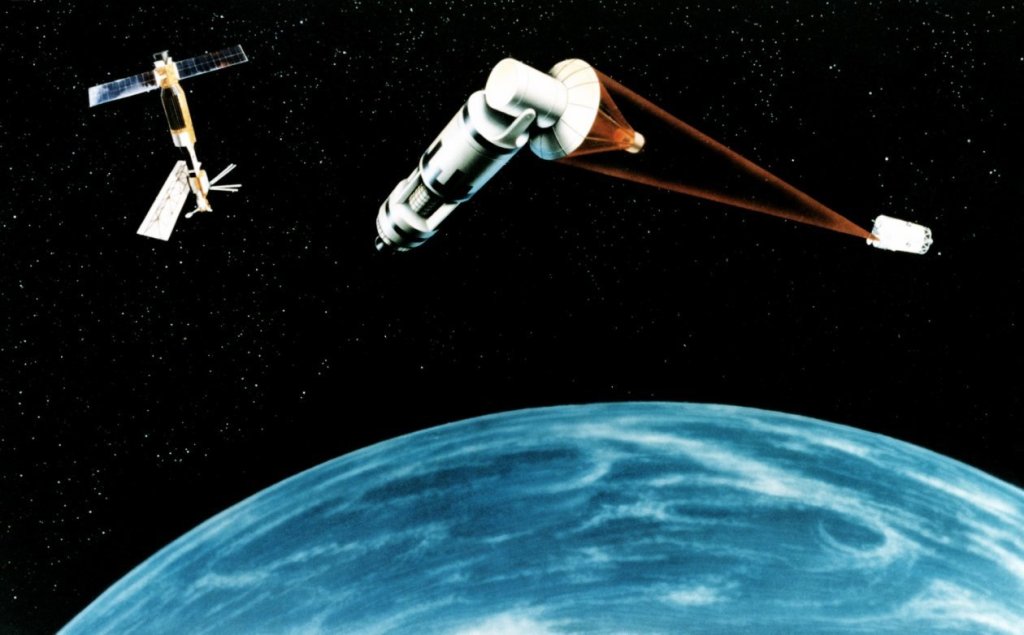

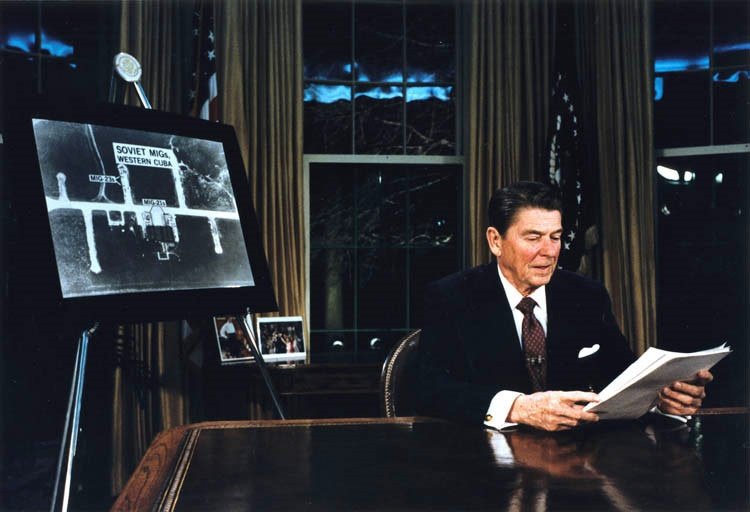

This quest became my full-time occupation after the March 23, 1983 speech by President Reagan in which he called for a program “to make nuclear weapons impotent and obsolete.” As a result, I was asked by Harold Agnew, the former head of Los Alamos Lab, to help put together a plan to implement the President’s challenge. The plan that was delivered to the President in September 1983 consisted of a collection of poorly defined technologies and called for a five-year $25 billion investment to answer the question of whether could someday be a defense. Because I had helped to create the plan, I was asked in 1984 to become the chief scientist for Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative. I found my assignment was primarily public relations as the actual research work was dominated by the question “will it make us safe,” and I spent many days and weeks trying to explain to the detractors what “it” was.

During this time, I often found myself in debates with notable opponents. I vividly remember my debate with Hans Bethe, Nobel Laureate in physics, who also happened to have been my quantum mechanics professor in 1961 at Cornell University. Our debate was published in Science Digest in an article, entitled “Can Star Wars make us safe?” Bethe answered no, and he was joined in his opinion by practically all of the academic scientists at the time. They argued that we had no plausible way to accomplish what they thought was Reagan’s goal to protect all of us from the threat of nuclear tipped ballistic missiles. I argued that the answer was yes, but I changed the definition of the goal to become more in keeping with my understanding of what Reagan really wanted, and in keeping with the wisdom of Dyson. Today, the demands for the protection against the threat are much more complex including hypersonic missiles, cruise missiles, anti-satellite weapons, and cyber-attacks. In fact, one of the scariest threats would be contagious bio weapons spread by swarms of crop sprayers launched from submarines near our coasts. But my answer to the question, will “it” make us safe, is still in the affirmative.

As before, the arms control experts have spoken out to explain “it” just cannot be done. They repeat the same old arguments that it won’t work, it is too expensive, and it will create entirely new strategic instabilities. The question I asked at the time was “what is it,” and I think that is the right question to be considered now.

So, what about now? Are we still arguing about “it” without understanding what it is? In my view, it is not about how to win the ultimate global war using space-based weapons, but it is to prevent war. Maybe with the recent advances in technology, we can find new ways to accomplish that through a new approach to deterrence that involves a shared approach to a stable combination of defense and offense tech development. We will need to first accomplish a breakthrough in vastly improved trusted communication and decision making in the face of confusion, chaos, threats, and fundamental disagreements. With the proliferation of advanced offensive weapon technology, we need to try to find a new more hopeful path. Maybe there could be some stable system to prevent war through technology enhanced information sharing, reduced offensive threats, and deterrence that will prevent the initial steps toward war.

But I recall Bethe’s final argument in our debate was that any defense could not be trusted since it could not be tested under realistic conditions. I argued that we already have learned to live with deterrence that cannot be realistically tested, since that has to be a question of psychology involving human decision making. It is conceivable that complex reasoning-based information management and decision making can be assisted through AI that could carry out simulated tests of a semi-infinite number of complex combinations of events and human decision making.

I remember when I was asked by Harold Agnew to lead the group to deliver a plan for the beam weapons component of the SDI. He said in a hushed tone that I had to take very seriously his warning that my job would be “very, very dangerous.” He said I could easily be trampled by the stampede of contractors going after funding. He was not encouraging to say the least, and in a matter of weeks he walked away from involvement. He never understood the Reagan goal of the program and was definitely opposed to any thought of nuclear weapons abolition. His concept of safety was the threat of destruction.

The “it” is still hard to define and has not become easier, but President Trump says there should be a way to protect us, and there should not be any limit to the amount of investment. Maybe the “it” is a safe future world, and then the question is… can the Golden Dome make us safe? Let’s see what “it” is in the plan soon to be delivered to the President.