Imagine a computer glitch that sends a signal from the space-based missile launch warning system that an ICBM attack has begun. An automated Artificial Intelligence (AI) data analysis and decision battle management center responds in seconds. The result is the beginning of an exchange of thousands of nuclear tipped missiles that destroys life on this planet.

“If only AI

could tell us what to do…”

Do we want high-consequence decision making under time urgent confusing conditions to be made by AI without a human in the loop? Will we trust the judgment of the non-human decisionmaker if it is contrary to the subjective feelings of the humans in charge? In the sci-fi movie 2001, Hal the computer responded to an instruction with the famous response, “I’m sorry, Dave, but I can’t do that.” In the future, Hal may send the message, “I’m sorry, Dave, that I destroyed the world, but I had no choice.”

High-consequence decision making is a challenge for humans under the best of conditions, but often the situation is additionally constrained by sleep deprivation, anxiety, stress, miscommunication, misunderstandings, superstitions, irrational fear, and other demands, mean decisions might be better carried out by Hal. Maybe a decision devoid of feelings of regret would be superior to the judgments of irrational overwrought human beings.

Throughout history, humans have made mistakes with vital decisions. Significant negative outcomes have been the result. In this post I describe several instances where, in my opinion, the key decision makers would have been more successful with a real time extensive data collection and AI analysis coupled with a decision system provided by one or more high performance 20-watt computers, namely their brains. On the other hand, in some cases, humans may not always be the best qualified to make the final decisions due to their deeply held beliefs and biases.

One highly recognized important decision (that some historians describe as the decision that “saved the world”) took place in September 1983. Stanislav Petrov, the person in charge of operating the data monitoring from the Soviet’s satellite early warning system, detected signals indicating an ICBM attack. He decided it was a false alarm and did not initiate the events that could have resulted in nuclear war.

Contrast this with the 1988 incident when the USS Vincennes mistakenly shot down an Iranian passenger jet. The commander faced a mix of accurate and misleading information, resulting in a tragic error. In such a scenario, AI could potentially offer real-time analysis and reduce human error—provided it’s designed to support rather than replace human judgment.

AI has the potential to enhance decision-making, especially when combined with human expertise. There are situations where human biases, deeply ingrained beliefs, and emotional responses may cloud judgment, making AI’s objectivity an asset.

The importance of human decision making played a major role during the 1980s when I was involved in developing the battle management plans for Ronald Reagan’s proposed missile defense program, labeled in the press as Star Wars. When faced with the detection of a Soviet missile attack, Reagan decided it would be better to defend rather than to retaliate. The defense against a highly capable ICBM attack would require deciding in minutes to initiate the launch of a defensive system. AI wasn’t available then, but had it been, would we have turned to it for a data handling, analysis, and decision process to help determine if an attack was real and help plan our response? Perhaps such split-second decisions in the face of overwhelming complexity would have been better handled by a combination of AI and human judgment than by humans alone.

Another example from history illustrates how life and death decisions can be made incorrectly. The question is, would having AI assistance have made any difference in the outcome? In my role as the Strategic Defense Initiative chief scientist, I was assigned to negotiate deals to advance the SDI concept, so I met with Karl Beckurts, the research director of Siemens, one of the largest electronics companies in the world. My assignment was to persuade him to have his company join us. We had a rather fancy lunch, and our discussion was quite pleasant, but he made it clear that he, speaking for his corporate leadership, had decided that they had no interest in working with the United States on the SDI program. That lunch may have cost him his life.

On July 9, 1986, in Bonn, West Germany, Beckurts was killed. A remote-controlled bomb detonated as his limo passed by a tree on his established route to work. A seven-page letter from the Red Army Faction (RAF), undoubtedly under the direction of the KGB, was found near the location of the bombing. The letter said that he had been killed because he was preparing to support Ronald Reagan’s program to develop a space-based missile defense program called the Strategic Defense Initiative.

The Soviet decision to take Beckurts’ life is an example of flawed human decision making based on false perceptions and misunderstandings. But, even if AI support had been available to the Soviets during the 1980s, I doubt they would have turned to it. You see, they had already made up their minds about the threat from SDI.

Much like the Germans, both the French and British decided not to work with the United States on developing missile defense. One nation made a different decision. This country was interested in engaging in a joint program to develop a long-range missile defense system, and they were willing to share the cost with us. Their goal was not to help us, but to defend themselves. Their decision process seemed to me to be straightforward, not requiring any complex decision process. They were surrounded by enemies who posed an existential missile threat. The cooperative program was called Arrow, and we established a development program, that has been continually advanced over the years. The most advanced version, Arrow 3, a Boeing/Israel Aerospace Industries program is reported to have successfully intercepted a ballistic missile attack from Iran, and their defense system is now being upgraded. It appears that the Israeli decision paid off.

I want to close by emphasizing that I believe that human decision-making processes are the best way to deal with the ambiguity of complex issues, but in some cases, people could also benefit from technical assistance provided by AI. Ten years ago, I patented a concept for human brain cognitive enhancement. I explore this idea in my latest science fiction novel, The Dragon’s Brain, which will be released in October 2024. I am working on the final book in this series in which I consider whether our decision makers have the wisdom, perspective, and values to make the right decisions to preserve what seems to be becoming an increasingly unstable world. Today Iran is threatening to launch a retaliatory attack on Israel and President Biden is trying to persuade Netanyahu to agree to an end to the war in Gaza. By the time you read this, the decisions of people based on their own brains–without any help from computers—could impact world peace.

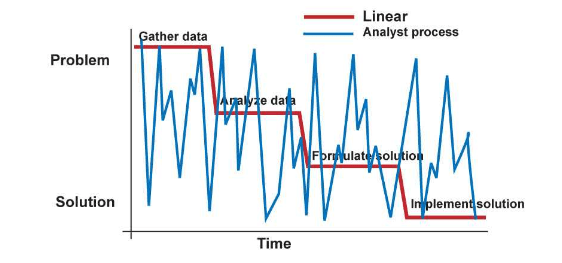

Seventeen years ago, I was invited to give a presentation to a group of intelligence analysts at the Joint Military Intelligence College. At that time, I was managing the Advanced Concepts Group at Sandia National Labs, and my group was focusing much of our attention on emerging threats. A current issue was what was called “the global war on terrorism.” This war began in Afghanistan in 2001 after the Al-Qaeda attack and continued for 20 years. During that period, it expanded to include Iraq in 2003 with one justification being the belief that Iraq was linked to Al-Qaeda.

Seventeen years ago, I was invited to give a presentation to a group of intelligence analysts at the Joint Military Intelligence College. At that time, I was managing the Advanced Concepts Group at Sandia National Labs, and my group was focusing much of our attention on emerging threats. A current issue was what was called “the global war on terrorism.” This war began in Afghanistan in 2001 after the Al-Qaeda attack and continued for 20 years. During that period, it expanded to include Iraq in 2003 with one justification being the belief that Iraq was linked to Al-Qaeda.