In 1977, our Sandia team responded to the competition with Russia with our own claim of successful e beam driven fusion only one year after Rudakov’s announcement. Our concept was called “magnetic thermal insulation,” and our experimental result called “the Phi target” was announced to have produced a similar number of neutrons as the Rudakov claim one year earlier. The basic idea was not amenable to simple analysis, since it involved extremely complex physics of the plasma stability of thermal insulation. At our annual review from the government and outside experts we learned it was not favorable to the plasma physics theory community, but is in fact a key attribute of today’s Sandia inertial confinement fusion program. We made no mention of the so-called Rudakov secret target, and both groups went different directions. An article in “Physics Today” helped to excite the feeling of competition between the two groups with a title: “Sandia and Kurchatov groups claim beam fusion” and we were happy to receive continuing funding, in no small part due to the “help” from our Russian friends.

Those of us with weapons clearances were sworn to protect the radiation drive concept, but this left room for speculation by the media. For instance one story claimed, “The Soviets are nearing a breakthrough in developing nuclear weapons 100 times more powerful than the largest current weapon–a gigaton hydrogen bomb–a doomsday bomb that could destroy the world in one blow.” Two prominent U.S. weapons physicists argued in private over whether to acknowledge the revealed concept and eventually the weapons community acknowledged that there was no longer a secret to protect. Both countries were off and running in a race to be the first to prove the concept that was called the hohlraum secret, except by then the very concept of radiation coupling to a fusion target had disappeared from any public discussion, and the concept no longer seemed to exist in the Soviet Union, or at least no more was said about it.

The technical problem we both faced became how to get enough energy into the hohlraum fast enough to do the job. Our simple calculations showed that would require 1000 TW, and that was almost inconceivable. We thought maybe the combination of radiation drive and magnetic thermal insulation might permit ignition at 100 TW. At an international fusion conference in 1975, Rudakov had already published a concept for an e beam fusion reactor and the e beam was certainly not in the 1000 TW class. Rudakov was not alone in rather wild extrapolation, since in 1974 we had already applied for a U.S. patent on an e beam fusion reactor concept and the patent was award in 1975 and expired in 1992, so I never got any royalties. I did publish a “Scientific American” article in 1978 entitled “Fusion Power with Particle Beams” and similar to the continuing saga of fusion “breakthroughs” claimed frequently, success was only 20 years away.

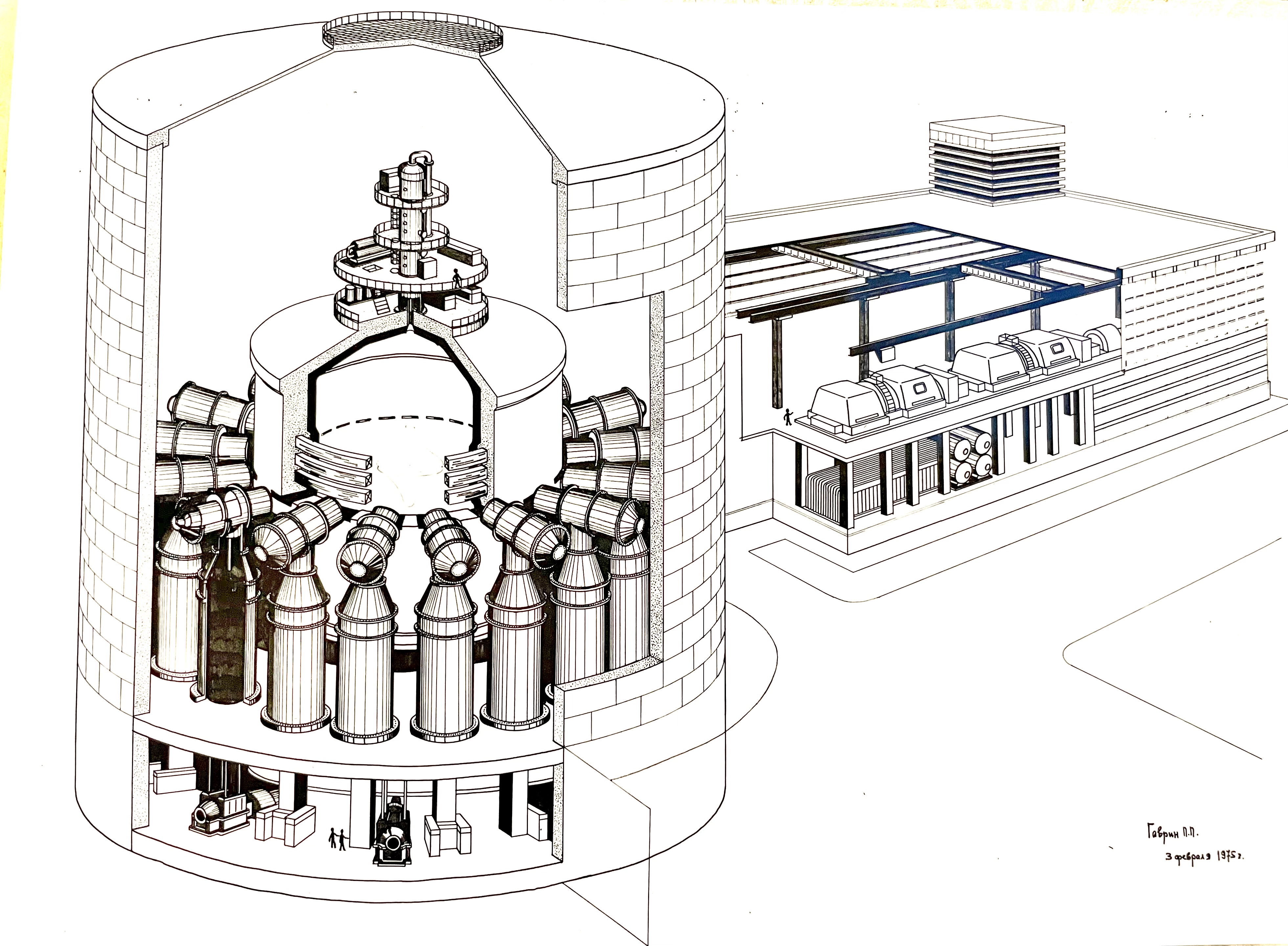

By 1979, the Soviets announced that they were operating the first module of their machine called Angara 5, and they claimed as reported in “Pravda,” “When it is completed we hope to obtain a controlled thermonuclear reaction…producing more energy than it consumes … demonstrate that an industrial pilot plant can be built.” The “New York Times” picked up the story with a front page article “Soviet Reports Major Step toward a Fusion Plant.” The article went on to say the similar facility at Sandia is expected to start operation in a year and cited “the middle 1980s as a possible time when researchers may achieve a breakeven point … and another before a fusion reactor produces more power than it uses, opening the way for the production of a useful energy source.”

In 1981, the U.S. Department of Energy advertised their inertial confinement fusion program as proceeding toward a 1987 goal when, “ignition experiments at Sandia and at the Lawrence Livermore Lab, provided a simultaneous evaluation of trade-offs between lasers and particle beam drivers.” The Kurchatov group continued to innovate ideas for electron beams, and our group changed the focused beam approach from electrons to ions that could provide a more certain method to heat a thin shell. We pressed ahead with construction plans. Our timing for the change to ions was rather fortunate, because the Department of Energy had already decided our electron beam approach was a dead end, but I convinced the head of energy research that I was also “negative on electrons and positive about ions.” The race was on, and the participants believed the outcome was certain to be resolved in only a few more years.

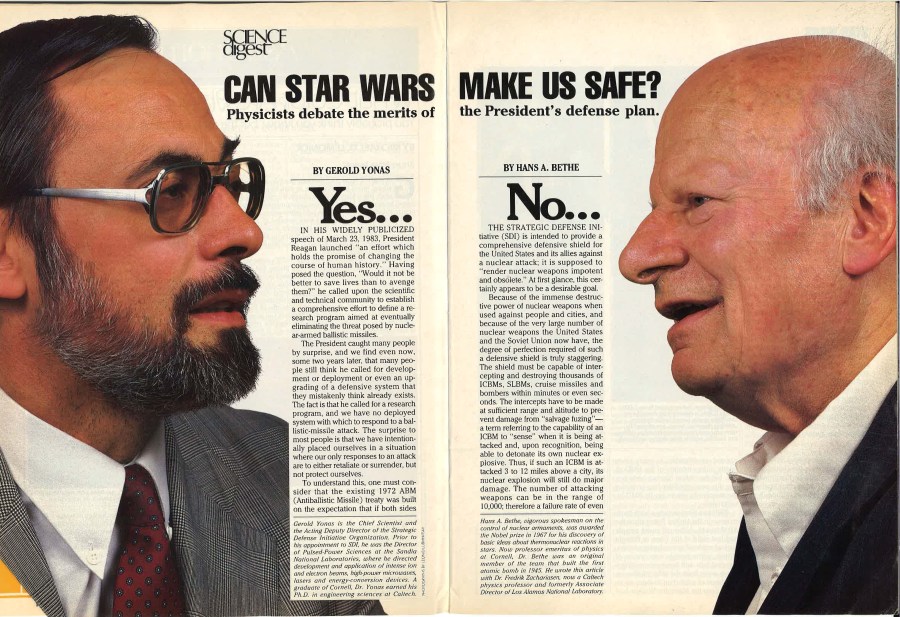

By 1983, Rudakov’s group was silent about any more hohlraum ideas, and for the next 10 years I was not involved in the Sandia program. After Ronald Reagan’s famous speech on March 23, 1983, to embark on a fundamental change in our strategic weapons investments from offense to defense, I was asked by former Los Alamos lab director Harold Agnew to work for three months with a team of experts from the labs and industry to put together a five-year Pentagon directed energy weapon plan. One concept was that a low altitude space-based constellation of powerful chemical lasers could attack and destroy the giant SS 18 boosters as they slowly rose above the atmosphere. There were many other concepts that were “imaginative.” After only a short time, Agnew told me he had become convinced there was “no pony in that pile of horse droppings,” and he became uninvolved in the process.

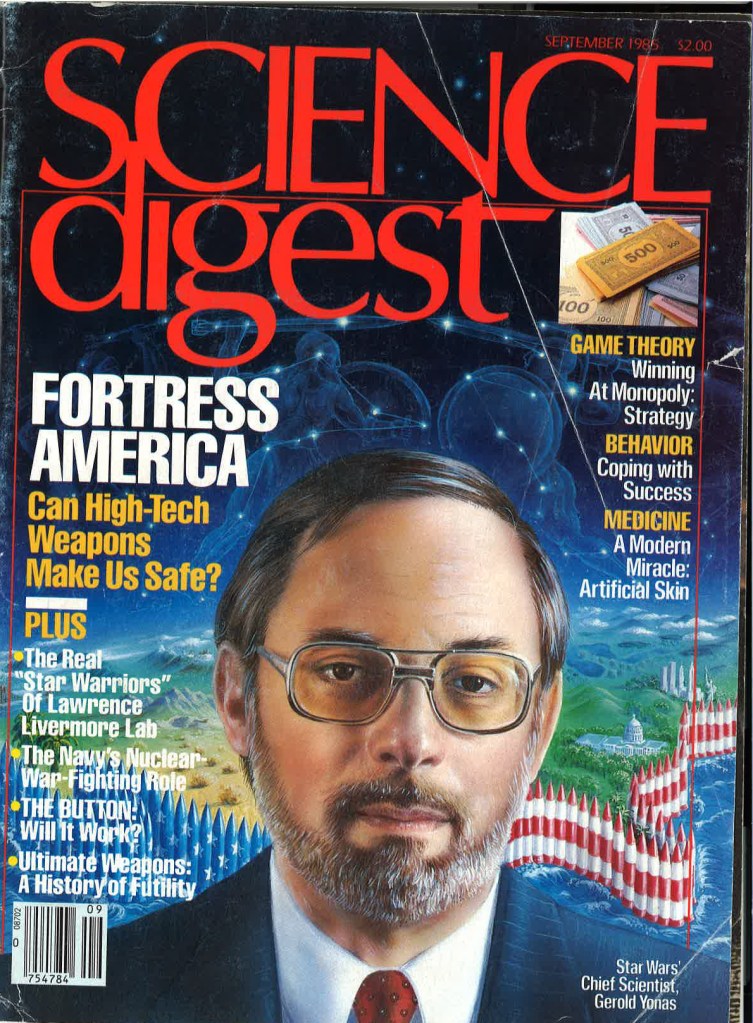

We did complete a plan that we delivered to the president in the fall of 1983, and it became part of the $25 billion five-year proposal that went to the congress and Secretary of Defense Weinberger was dedicated to make it a reality. By then I was sure the entire venture was going nowhere, but the president had decided that missile defense could make nuclear weapons “impotent and obsolete” and few people realized that he hated nuclear weapons as much as he disliked Soviet communism. A few months later, I was chosen by General James Abrahamson as his acting deputy and the Chief Scientist for Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, AKA Star Wars program, with an assignment to help make the president’s vision a reality.

Much of my two years in the Pentagon involved defending the program that I claimed was research to resolve the enormous number of questions about technology that the president claimed was almost ready for deployment. He repeatedly said he wanted to share everything we learned with the Russians if they would agree with us to give up all our nuclear weapons. The scientific community, including many of the people I had worked with, were inclined to accept Agnew’s opinion, but one MIT professor advocated that we keep very secret anything we learned of value, but that we share everything that did not work. It seemed to me two years later that the technology was no closer than when we had started. The advances in offensive countermeasures moved ahead much more rapidly than the defense technologies. There were, however, actually two true believers that did remain, and one was the Ronald Reagan and the other was Mikhail Gorbachev, but that is yet a different story I published in an article entitled “Its Laboratory or Goodbye.”

After I left the Pentagon, and after a three years trying to manage defense contracts at a private sector defense contractor, I conclusively demonstrated my inability to manage cash flow. When I learned that Al Narath, who had hired me at Sandia in 1972 had returned to Sandia after a stay at Bell Labs, I decided to rejoin him at Sandia. Eventually I was reassigned back to the fusion program, and Narath, who had supported me in my early quest based on the promise of pulsed power engineering 20 years earlier, was becoming “a bit impatient.” Our work at Sandia had gone from the initial electron beam work in 1972, then on to EBFA, to the transition to ion beams on PBFA I, then the larger PBFA II that fired its first shot in 1985. The pulsed power technology was a success, but the problem was that the ion beam generation and focusing research was in a rut, and now a miracle was needed to get to 100TW and even the more daunting challenge of 1000TW.

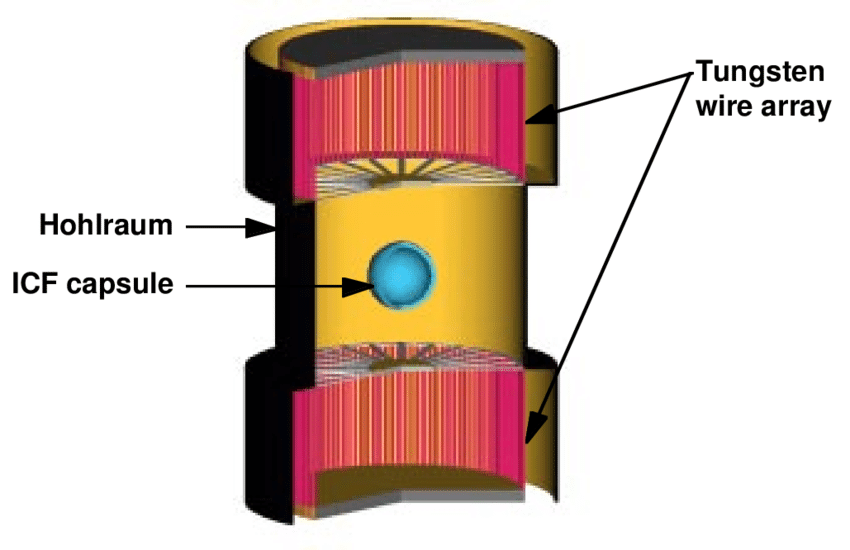

Then the brilliant discovery involving many very creative scientists at several labs was that a pulsed power driven Z pinch could produce levels of radiation above 100 TW to drive a fusion capsule. The basic idea of the Z pinch is to slowly build up the power in a magnetic field that compresses and heats a plasma that implodes to high density and temperature, and then becomes a powerful source of radiation as it collapses on itself. The PBFA II sign came down, and the machined was renamed Z. The ion beam approach was discontinued in a burst of enthusiasm for the new way ahead.

After the demonstration of what I claimed was “the most powerful X-ray source in the world,” my marketing juices were flowing again. I proposed to use a two sided Z pinch hohlraum concept with an even larger machine I called X-1 that probably would require a $1 billion investment. I advertised this idea in 1998 in my second “Scientific American” article entitled “Fusion and the Z Pinch” 20 years after my first installment in that magazine article on particle beam fusion.

The basic idea was to employ two identical Z pinches to drive a hohlraum at radiation power levels approaching 1000TW and with a pulse duration of 10 billionths of a second that could deliver 10 million joules to a target. That appeared from calculations to be the right amount of energy to ignite fusion burning and obtain high output gain. I was convinced we could reach our goal before the laser program at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory could get there, but that competition did not make the Department of Energy happy since they had already decided that the National Ignition Fusion (NIF) laser approach was the right way as they brilliantly demonstrated last year, over 20 years after they convinced the DOE that I was wrong, as they achieved fusion burn demonstrated with NIF and two sided irradiation using 192 laser beams delivering almost 2 million joules to the hohlraum.

My marketing activity, however, resulted in my permanent removal by DOE from the program in 1998. My Russian friend also departed from their ICF program and he left the Kurchatov Institute and immigrated to the United States. His colleague Valentine Smirnov became the head of the Russian program that was concentrating on the Z pinch approach. The Sandia pulsed power program continued and prospered without my further interference, with an upgrade leading to improvement in machine performance and diagnostics leading to several scientific discoveries related to materials at extreme temperatures and pressures.

Now the Sandia program has changed course again and is focusing on a new concept called MagLIF for ignition based on a Z pinch to implode a magnetic thermally insulated and laser preheated cylindrical target. Ironically, the use of magnetic insulation in a pulsed power driven target was what I had proposed with electron beams in the Phi target.

The hohlraum is essential to the NIF laser fusion approach, but is no longer part of the chosen concept at Sandia. I would, however, not be surprised if the advantages of trapped and symmetric radiation-driven implosion may be reinvented someday, possibly in China. The history of foreign competition seems to be repeating itself as the Chinese have claimed to be building a machine “20 times more powerful than Z,” which is probably an exaggeration, but I am sure it will be in the 1000TW range–that is if it really is funded. Their publications demonstrate a thorough knowledge and ability to harness the needed modern pulsed power technology.

It has been 25 years since the Sandia approach became the use of the Z pinch, and to celebrate that event, the seven Sandia pulsed power directors who have provided leadership for the pulsed power science program since 1978, came together last year to share their memories and provide the incentive to continue the journey on a path I started over 50 years ago. The advance of science and technology continues, but sadly it seems that human behavior has not improved that much. It seems now that Reagan and Gorbachev had a rather good idea about eliminating nuclear weapons after all.