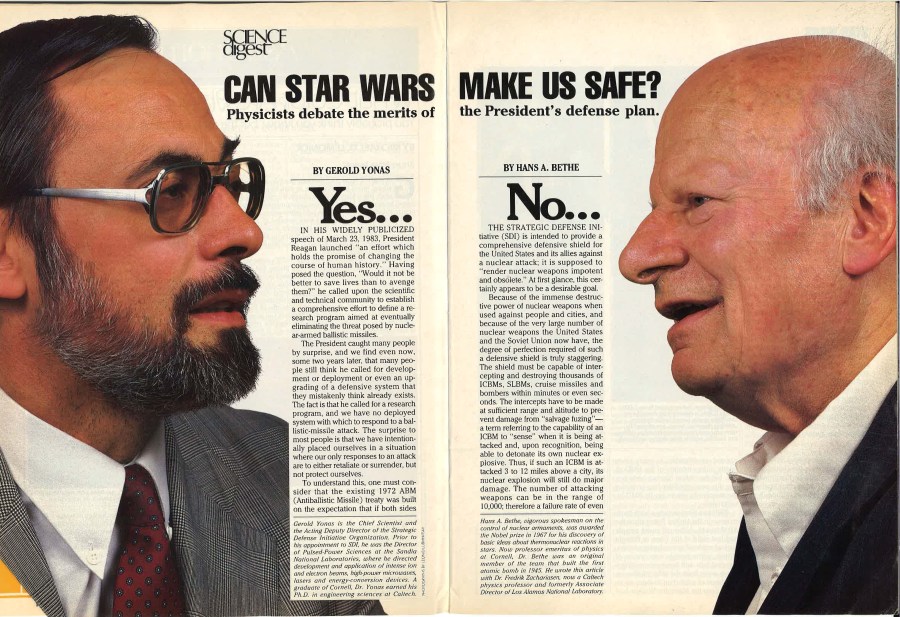

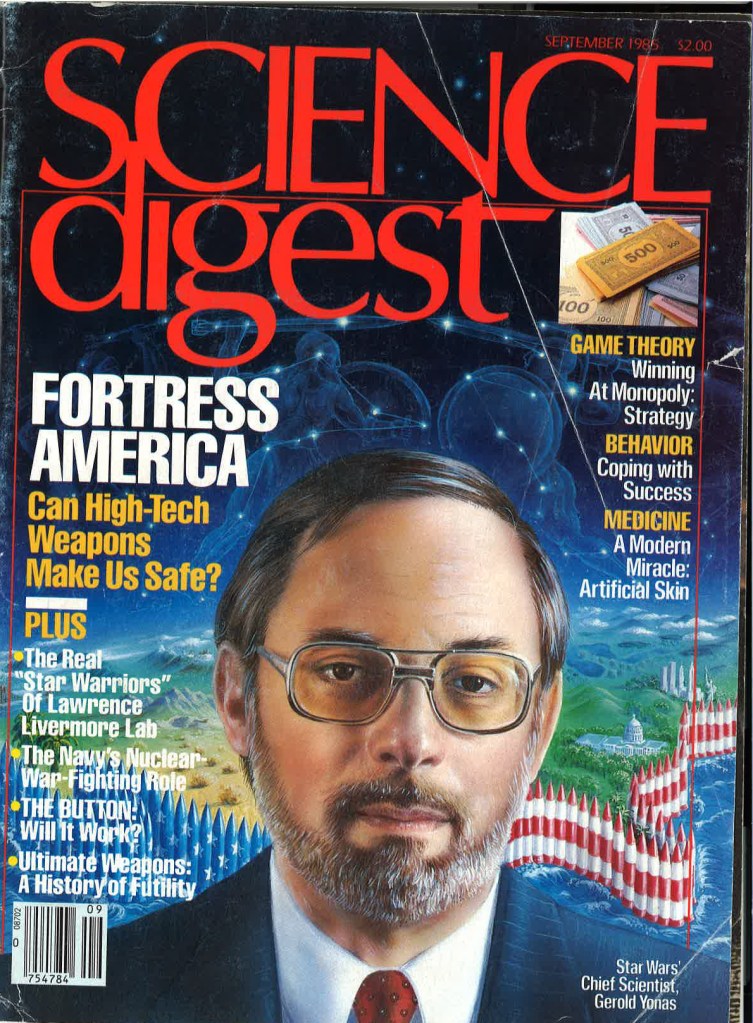

In 1985, the magazine “Science Digest” featured a debate between me and Hans Bethe, the 1967 Nobel Prize winner in physics and my former Cornell University undergraduate quantum mechanics physics professor. The question was whether President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, SDI, could be effective against nuclear tipped Soviet missiles. Bethe’s answer was a definite, “No.”

Bethe’s most persuasive argument was, “The entire system could never be tested under circumstances that were remotely realistic.” He did not wish to tackle the psychology of deterrence. He focused on the technical issues instead.

The United States was already living with the concept of mutually assured destruction, which I knew could not be tested either. I argued it was too soon to discuss the effectiveness of any hypothetical defense system. I believed a research program was justified and would be needed in order to influence the perception of a new and safer approach to strategic stability.

There was one area of technology development that concerned me––the requirement that the split-second events in a war would have to be managed by computer software. Back then I was basically Reagan’s Ray Gun Guy, and I did not know anything about testing software. Today, it looks like Bethe was right about the importance of testing. But there’s still something he missed.

Here’s where I think Bethe went astray: testing is all about technology, but deterrence is far more complicated. The vital issues in creating a credible deterrent are not just technology, but economics, social issues, political arrangements and psychology. I learned over the years that such problems really have no final solution, and continuing to pursue the answer often leads to alternating periods of hopeful optimism and depressing pessimism… and sometimes, but not always, real progress. My published opinion was that the outcome of the SDI program would “depend not only on the technology itself, but also on the extent to which the Soviet Union either agrees to mutual defense agreements and offense limitations…no definitive predictions of the outcome can be made.”

My feelings were ambivalent. I struggled to communicate the complexity of the issue to my scientific and political colleagues. I found it even more difficult to explain the questions surrounding SDI to the news media. But one person got it. He was a cartoonist.

In the 1980s, Berkeley Breathed, the cartoonist behind the series Bloom County, created a cartoon about me, the Chief Scientist of Reagan’s SDI, aka Star Wars program. He depicted me as a chubby penguin named Opus, who claimed that enormous sums of money would be needed to develop a “space defense gizmo.” When Opus learned that the unlimited money was not forthcoming, he screamed, “Physicists need Porsches too,” and then mused that maybe “the days of wines and roses are over.” Breathed understood the reality of my job.

I had been challenged with helping to put together a $25 billion, five-year plan for a research program to accomplish Reagan’s goal of “rendering nuclear weapons obsolete.” After the plan was finished and delivered to the Secretary of Defense, I wrote that even if the research was wildly successful, any workable missile defense would have to go along with a comprehensive arms control treaty that greatly reduced our own offensive capabilities as well as the threat. In spite of my published doubts, the following year I was asked by the newly chosen program’s manager, General James Abrahamson, to be his deputy and chief scientist. We brought together a distinguished advisory group including Edward Teller, the “father of the H bomb”, Bernard Schriever, retired four star general and the father of our nation’s first ballistic missiles that responded to the Soviet threat posed by Sputnik in 1957, Simon Ramo, the father of the engineering behind that first ballistic missile technology, Fred Seitz, former head of the National Academy of Sciences, and me.

During my two years in the Pentagon, I was faced not only with many serious detractors, but also with many incidents that could have been the source of high anxiety. I realized the contradictions, irony and exaggeration in the program were inescapable. I managed to approach the many stressful moments with humor that I often expressed in satirical memos and comments that were not always appreciated by my boss. But when dealing with complicated issues, there are no simple solutions. The best you can do is hang on to your sense of humor and keep trying to help other people understand your point of view.

As a cartoonist, Breathed understands that. His fictionalized depiction of the Star Wars dilemma summed up the situation succinctly. Reflecting on his cartoons years later, I wondered if perhaps Breathed had the answer to explaining the ambivalence that I faced during my time in the SDI program. In fact, the contradictory issues related to nuclear deterrence are something all scientists working in national defense face.

So, taking my inspiration from Breathed’s penguin, I have decided to try my hand at writing fiction. This spring, I will launch the first in a series of novels about the complex interaction between science and politics. Stay tuned for more information in future posts.