Heraclitus had many famous quotes, but the one I often remember is, “No man ever steps in the same river twice. For it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” My take away from this is relevant to many of the complex problems I have worked with over my 50 odd years of dealing with various science and technology problems. Also, I can claim without contradiction that my career has never been blemished with even a single success.

For some reason, I always seemed to be interested in really challenging problems that were limited by not just engineering and physics, but also by constraints of politics, economics, and human decision making. I have written about this general class of problems that are best described as “wicked.” They are characterized as not having any closed form solution. Working on such problems provides the participants with alternating experiences of euphoria and utter depression. Maybe that is why poor Heraclitus had a problem crossing a river.

People in charge of maintaining the United States’ nuclear weapons stockpile are facing a particularly wicked problem. Their job is to assure that the weapons are safe, secure, and reliable… but without the ability to fully test them by detonating any of these weapons. This approach is called Quantification of Margins and Uncertainty (QMU). It is a process of highly diagnosed but sub critical experiments and comprehensive computer simulations to allow decision making about the risk involved in the performance and reliability of the stockpile.

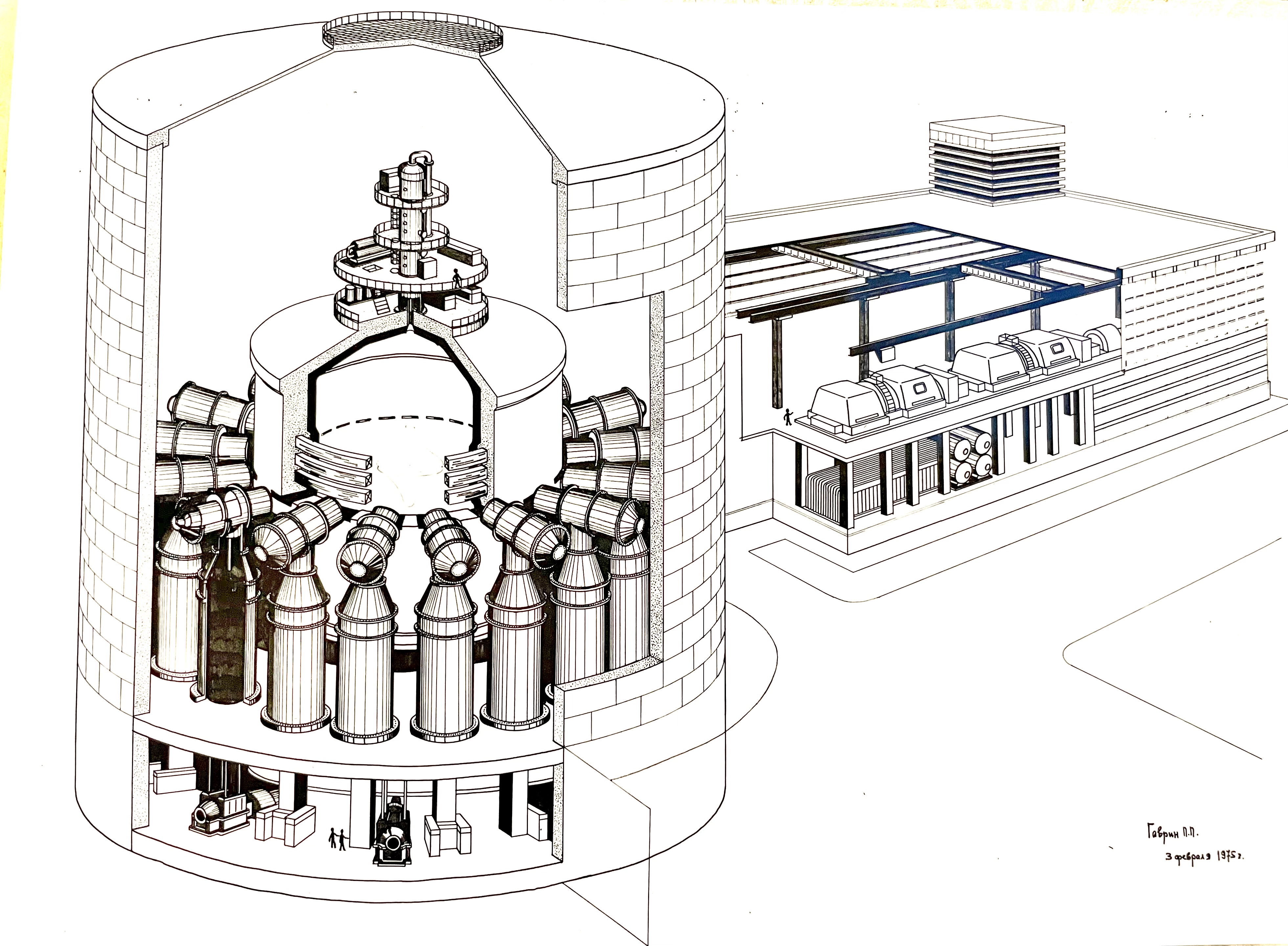

An extremely important and challenging aspect of this program is the use of lasers to ignite fusion ignition in the laboratory. The recent experiment at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) recently demonstrated fusion ignition with more energy output than delivered to the target by the lasers. This is the first time that actual “fusion ignition” has been achieved in a lab.

In my Feb.23 post “Fusion Fact or Fiction,” I explained the seemingly “miraculous” achievement involving many tradeoffs on nonlinear variables adjusted over years of complex experiments and calculations requiring continuing political support with ever-increasing budgets. I stated then (and as far as I know now) the achievement has yet to be repeated. The lab director explained recently, “We haven’t had the kind of perfect capsule that we had in December.” Perfect capsules will require a “perfect” budget.

An additional issue is the performance of the laser. Pushing the laser to its limits causes damage to the optical system that is expensive and time consuming to fix. There is also the political pressure created by the association of fusion research with the desire to develop the ultimate clean, cheap, unlimited source of energy.

So, how can leaders deal with this wicked problem? I think the methodology that will be useful is QMU that focuses on establishing the needed margins of performance of all the components of NIF experiments that will have uncertain outcomes. Each experiment will be a different man stepping into a different river. Heraclitus would certainly get his feet wet, but he might get swept away.