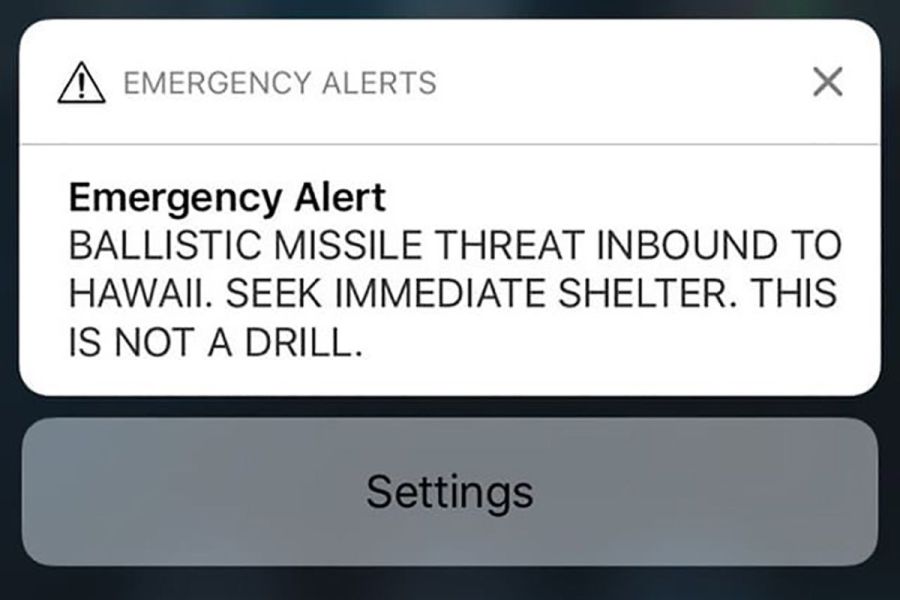

In January, an early-morning emergency alert mistakenly warned people in Hawaii of an incoming ballistic missile attack. Less than an hour later the warning was revoked, but the mistake started a panic. More importantly, what if the missile attack were real?

Several commentators have dealt with the question of what if the missile attack on Hawaii had been real. Our military would have known almost immediately that a real missile was launched and on its way. The flight time from North Korea would have been 18 minutes and in that time we could activate our responses and send our interceptors on their way. But does that mean that the probability of stopping the attack was so high that there was no reason for fear? One commentator, without even mentioning defense, suggested that people should duck and cover. That was the “method” for surviving nuclear attack that we practiced when I was in junior high school.

Others in the military have written that our missile defenses would be activated and interceptors would be launched and could destroy a single attacking missile. This assumes that our deployments are effective, the right decisions could be made in time, and that the response would be to launch enough interceptors to increase the probability of successful defense. But what if the first missile was really only one more test and the missile landed harmlessly in the ocean? Or maybe this was part of a strategy of seeing how fast and how well we could respond? And what if the intercept really was successful? Would we then retaliate or just send a warning?

But such issues have always been on the table during the decades of deterrence- based strategy. That is until Ronald Reagan questioned the entire basis for our survival. He asked if we could develop a high-tech defense based on assured survival instead of assured destruction. His idea was totally out of favor with all of his strategic weapons advisors who believed that the threat of total mutual guaranteed annihilation would be the only way to achieve deterrence.

based strategy. That is until Ronald Reagan questioned the entire basis for our survival. He asked if we could develop a high-tech defense based on assured survival instead of assured destruction. His idea was totally out of favor with all of his strategic weapons advisors who believed that the threat of total mutual guaranteed annihilation would be the only way to achieve deterrence.

Now all of that seems to be no longer acceptable and nuclear weapons proliferation is a growth industry. Our new nuclear posture review is calling for more modern low-yield nuclear weapons to strengthen deterrence since Russia and China have adopted this approach. The argument against assured destruction is that deterrence is no longer credible if the other side has developed more usable low-yield nukes and is increasingly relying on them for deterrence. So the argument is that by making our ability to wage nuclear war more credible, our deterrence is more credible. No more talk of irrevocable destruction of society.

But what about Reagan’s 1983 concept of reducing the nuclear stockpiles and creating more credible defense? As I explain in my book “Death Rays and Delusions,” the needed technology was way off in the future and we were not ready to move in this revolutionary direction. But now 35 years later we have made dramatic progress in sensors, platforms and interceptor missiles so effective defense should be taken more seriously than crawling under desks.

cooperation and a conviction to abolish nuclear weapons. He wanted to move ahead with SDI that he thought was close to deployment, and share SDI with the Soviets. Secretary of State George Schultz, his principal adviser, had recommended that “we trade the sleeves of our vest and make them think they got an overcoat.”

cooperation and a conviction to abolish nuclear weapons. He wanted to move ahead with SDI that he thought was close to deployment, and share SDI with the Soviets. Secretary of State George Schultz, his principal adviser, had recommended that “we trade the sleeves of our vest and make them think they got an overcoat.”