We live in a world haunted by wicked problems—problems that mutate, multiply, and resist every attempt at resolution. Climate collapse. Authoritarian drift. AI accelerating beyond oversight. Debt spirals. War without end. Each of these crises feeds on the others, creating a Gordian knot that neither our leaders nor our institutions seem able to untangle.

What can be done?

One idea, admittedly audacious, is to take a lesson from history. In 1953, President Eisenhower launched Project Solarium, a bold experiment in structured strategic debate. Three teams of experts—each representing a different philosophy toward Soviet containment—were asked to develop, argue, and defend their strategies. Eisenhower didn’t pick favorites; he wanted the sharpest disagreements and clearest thinking to shape America’s Cold War policy. The outcome helped solidify the doctrine of containment, which guided U.S. policy for decades.

Could we do something similar today—only smarter, faster, and more inclusive?

That’s the premise of a Solarium 2.0. Not a political stunt or top-down policy declaration, but a structured process to think our way through global dilemmas. Teams of diverse thinkers—equipped with AI-enhanced reasoning tools (software that helps analyze data, challenge assumptions, and model outcomes in real-time)—would be guided by an experimental new concept: a values-based AI coach. This coach, rather than dictating answers, prompts participants to consider ethical frames, recognize cognitive bias, and evaluate decisions through shared human values like justice, sustainability, and long-term resilience. Why a coach? Because even smart, ethical people face cognitive overload, fall into groupthink, or overlook long-term consequences—especially under stress. A values-based AI coach doesn’t replace human judgment; it enhances it by prompting reflection, highlighting ethical dimensions, and encouraging diverse viewpoints in real time.

It’s part war game (testing how different strategies play out under pressure), part design studio (developing novel solutions), and part constitutional convention (re-examining foundational assumptions and frameworks for action). The goal isn’t to draft legal documents but to explore better ways to think, act, and collaborate in a world of accelerating complexity.

But wait—who gets to play? Who chooses the questions? Why should anyone listen?

These are critical questions. And they lead to a bigger one: Should the new Solarium be national or global?

Solarium 2.0 is envisioned as an international initiative, drawing participants from multiple countries and cultural perspectives. Today’s decision-makers—men like Putin, Trump, Netanyahu—often play zero-sum games. But our survival may depend on win/win solutions. We may not have an Eisenhower today. But we can build the process he pioneered—updated for our era.

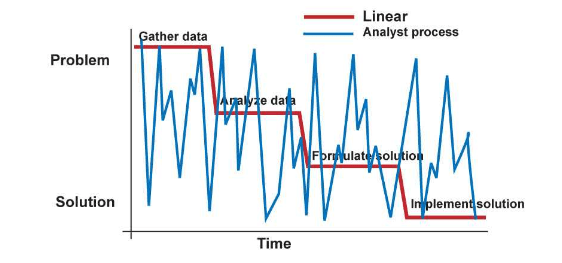

AI-assisted collective intelligence—humans working with AI systems to make better group decisions—isn’t science fiction. It’s a growing research field. But most systems today focus on narrow tasks or post-hoc analysis. What we need is a leap forward: real-time human-AI decision-making for wicked problems, with the AI acting not as oracle, but as orchestrator.

In a 2024 review of human-AI collaboration published in Intelligent-Based Systems, Hao Cui—a leading researcher in multi-agent systems—surveyed dozens of experiments. Most involved controlled environments and constrained tasks. But none attempted a live simulation of high-stakes, global-scale problem-solving under cognitive load. Why not? Possibly because of technical hurdles—or perhaps because we’ve lacked the will to convene the right people with the right tools.

That’s why I’m calling for a bold experiment: the Solarium 2.0 War Game.

Convene it under the auspices of a respected neutral body—such as the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine—and draw participants from national labs, forward-thinking companies, and leading universities. Equip them with emerging AI platforms designed not just for speed or scale, but for principled, values-aligned decision support. Use real-world scenarios, real time constraints, and real disagreement.

We’ve theorized enough. Now it’s time to find out:

Can we do better—together?

(Disclosure: This document represents a collaboration of human and artificial intelligence. The illustration was created by AI.)

Seventeen years ago, I was invited to give a presentation to a group of intelligence analysts at the Joint Military Intelligence College. At that time, I was managing the Advanced Concepts Group at Sandia National Labs, and my group was focusing much of our attention on emerging threats. A current issue was what was called “the global war on terrorism.” This war began in Afghanistan in 2001 after the Al-Qaeda attack and continued for 20 years. During that period, it expanded to include Iraq in 2003 with one justification being the belief that Iraq was linked to Al-Qaeda.

Seventeen years ago, I was invited to give a presentation to a group of intelligence analysts at the Joint Military Intelligence College. At that time, I was managing the Advanced Concepts Group at Sandia National Labs, and my group was focusing much of our attention on emerging threats. A current issue was what was called “the global war on terrorism.” This war began in Afghanistan in 2001 after the Al-Qaeda attack and continued for 20 years. During that period, it expanded to include Iraq in 2003 with one justification being the belief that Iraq was linked to Al-Qaeda.