The importance of surprise has dominated the thinking of military strategists since beginning of conflict. For instance, the famous Chinese strategist Sun Tzu wrote in 500 BC, “Those who are skilled in producing surprise will win. Such tacticians are as versatile as the changes in heaven and earth.” In 1520, Niccolo Machiavelli wrote, “Nothing makes a leader greater than the capacity to guess the designs of the enemy.” In 1832, Prussian general and military theorist Carl von Clausewitz wrote, “Surprise is therefore not only the means to the attainment of numerical superiority, but it is also to be regarded as a substantive principle in itself.”

Modern military strategists take the issue of surprise very seriously when managing investments in technology and preparing for possible future conflicts. Over the years I participated as a contributor in several Defense Science Board studies and often found myself as a member of the red team. My job was to imagine what might be the counter to any of our advances in future technology. It was never a good way to make friends since my role as a red team member was to invent how and why the best ideas of the blue team would be thwarted. The goal of the science and technology red team was to imagine and analyze a possible future threat evolution based on analysis of the past and evaluation of present capabilities. Then the blue team was faced with planning to deal with this imagined future.

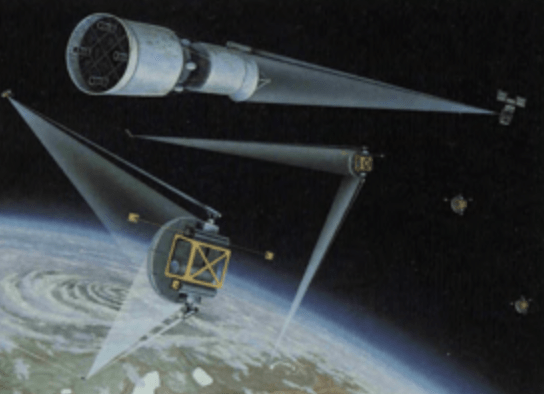

In 1988, the Pentagon published a document that described the status of Soviet technology and projected what might happen in the future. One future space weapon threat was the use of ground-based lasers and a distribution of space-based relay mirrors to provide lethal blows to space assets and missile launches in their early boost phase.

The Pentagon analysts projected that the space weapon threat shown in the illustration below might be deployed “after the year 2000,” but, as I explained in my last post, at the time neither the Soviets nor the Americans had the needed high power laser technology nor the space launch capabilities for any realistic space-based weapons. Over the past four decades, however, that technology has advanced to the point where the red team needs to reimagine what might be the new space-based threats as well as our new approaches to offense and defense. In today’s world of Russian attempts to return its empire to greatness, the defense planners are actively attempting to figure out what surprises they may face.

It really should not come as a surprise that Russia is now threatening its NATO neighbors with an intermediate range missile called Oreshnik and has demonstrated its operation against a Ukrainian city. This missile is a version of its ICBM capability to deliver multiple hypersonic independently target warheads or MIRV’s to a target. The attacking MIRV’s could be accompanied by multiple light weight decoys so that an effective interception in space would be extremely difficult. So, no surprise there. We have known about this sort of threat for a very long time. Our red teams should have been imagining the threat and persuading our blue teams to figure out how to defend against it.

The fact is that in 1983 when we put together a plan for the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) or popularly known as Reagan’s “Star Wars” program, we thought about these threats and concluded that we needed a means for intercepting the threat during the early part of its launch, namely its boost phase, and this required that we had to develop and deploy interceptor platforms in space.

The red team was ready for this hypothetical defense and reported that the defense platforms would be “sitting ducks” that would be easily destroyed by ground launched missiles. The blue team responded with hypothetical offensive and defensive moves. That meant that the result would become a full out space war, which could result in escalating exchanges leading to all out nuclear conflict.

No matter how effective the defense, the realistic outcome would likely be nuclear exchanges and total destruction for both sides. Many long term and experienced strategic thinkers explained that any notion of a victorious last move in an escalation exchange was a fallacy. They suggested that a more positive approach would be arms control agreements. Many people never really understood that both Reagan and Gorbachev were arms control advocates and were anxious to get rid of all nukes.

When I got the job as the chief scientist for the SDI program, I concluded that Reagan’s idea to share defenses and eventually eliminate all nuclear weapons was probably the only way out of this mess, and was unlikely, but was worth a try. When Reagan and Gorbachev met at Reykjavik in 1986, they almost agreed to rid the world of nuclear weapons, but at the last minute, although Gorbachev had no problem with SDI laboratory research, he demanded that the SDI stopped all testing in space.

Reagan’s advisors were surprised at Gorbachev’s emphatic and often repeated insistence that “it is the laboratory or goodbye.” I have concluded that he was afraid that his own military industrial complex would launch its giant Energia booster that was ready and waiting to launch a space laser research platform. Such a deployment, even if of marginal utility, would be a “Sputnik event.” Cold War historians have missed the point that he was more worried about his own technical experts that were prepared to initiate a space weapons race that would further contribute to the final implosion of the Soviet economy.

As it turned out, the Soviet Union collapsed because of its own weaknesses and without any real help from us and the threat went away. But now the threat seems to be back, as demonstrated by Russia’s advanced intercontinental ballistic missiles, its nuclear capable intermediate range missiles, and advanced war fighting methods such as information weapons to wage war. To add to this dilemma, China is not sitting idle but is rapidly advancing its strategic war fighting capabilities. The old ideas of two-party agreements seems to be obsolete.

So, as the famous arms control expert Herb York explained…. there really is no winning last move in an arms race. Instead, I believe that we need to consider a new approach—the road not taken. This imagined road will be an unfamiliar path filled with debris and pot holes that may never lead anywhere, but maybe there is a small chance that it might lead to agreements to avoid a global nuclear war. The problem of deterrence in this increasing complex world is so wicked, any success would be unexpected. In today’s world of technology advances coupled with confusion, chaos, and conflict, such an outcome could be the ultimate surprise.

The fact that the Soviets actually launched a weapon protype is seldom mentioned, especially by apologists such as Frank von Hippel. He would have us believe that the Soviet Union did not have a substantial ABM program comparable to the US Strategic Defense Initiative. This is far from the truth. ABM work started in the Soviet Union in the 1950s and was substantially accelerated in the 1970s. This ignores the launch on the Energya rocket on May 15, 1987 of a 1 MW CO2 laser called Polyus, with a mass of 80 tons. Gorbachev himself witnessed this launch.

The fate of Polyus is said to be that it deorbited due to a software error in the guidance system. An alternative account is that Gorbachev, realizing that this event would be observed and would collapse his anti-SDI campaign, ordered it deorbited.

LikeLike

I understood this one. But I think we are doomed.

LikeLike